One Man, Nine Cars, and Restoring Automobile History. The Buck Harness Story.

Before restoration shops, online forums, and the collector culture, there were people like Buck Harness— a collector and quiet craftsman who saved pieces of American automotive history one part at a time. Buck never set out to become a historian or a preservationist, but through decades of patient work, that is exactly what he became.

Early Life and Family Roots

Joseph Buckley “Buck” Harness was born on October 14, 1936, the youngest child of Alzere Marie and Glen William Harness, two lifelong residents of Henry County who raised their family with equal measures of work, resourcefulness, and quiet steadiness. His mother taught school. His father ran the local grocery store in the tiny town of Stotesbury, Missouri, where Buck spent his formative years stocking shelves, sweeping floors, and learning the ins and outs of small‑town life. His siblings, Leland and Gertrude, were both older than Buck, making him the baby of the family.

Service and Work Out West

After graduating from high school in 1956, Buck entered the Army. He didn’t speak much about his service, but when his time in uniform ended, he made Glendale, California, his home, where he worked as a machinist at Lockheed. Nine years later, he passed the fireman’s test and began the career that would define the rest of his working life. He remained in Glendale until retirement, when he returned to Clinton and Henry County, “back to the roots,” as he put it, even if those roots had changed. His parents and siblings were alive when he moved back, but all have since passed. Now, at age 89, he commented, “The roots are all gone now.”

In California, The Collector Emerges

California is also where something else took hold of him: the impulse to collect. Not just cars—though cars became the great passion of his life—but anything mechanical, historical, or simply intriguing. Lamps, Victrolas, statues, curiosities of all kinds. But the cars were different. They weren’t just objects to own; they were puzzles to solve, histories to explore, and machines to bring back to life with his own hands.

The First Spark

The steering wheel of his father’s 1936 Plymouth Coupe was his first experience sitting behind the wheel of a car. It was “exhilarating,” he said simply, remembering the experience fondly. Buck’s first car as a teenager was a Model T. He paid $15 for it. It hadn’t run in decades, but he coaxed it back to life, and the thrill of that moment never left him. Over time, the hobby grew into a calling.

Buck sought out the forgotten, the incomplete, and the nearly impossible: a Duesenberg chassis with a Buick engine, a Franklin buried under junk in a widow’s shed, an American Underslung pieced together from parts scattered across the country.

He restored them the hard way—down to the last nut and bolt—rebuilding engines, fabricating missing pieces, sanding and painting, upholstering interiors, and hunting for parts through swap meets and auto club newsletters long before the internet made such searches easy.

Why He Collected

Buck never collected for recognition or prestige, and he never entered contests. “I don’t care anything about that,” he said. He collected because old mechanical things made sense to him. Because they were built to be understood, repaired, and appreciated. Because bringing a silent machine back to life was, for him, a kind of personal triumph—one that brought him genuine pleasure.

A Barn Full of History

Today, nine of Buck’s cars remain in his barn, which he bought years ago—and which happened to come with a house. Through these vehicles, readers will step into the larger story of early American automobile history, a time when anyone with little more than a wrench, a sketchpad, and a heap of courage believed they could build the next great car. Some of those early dreamers succeeded spectacularly, but most vanished as quickly as they appeared.

As each car is explored, the story widens to discover the people and companies behind them. Buck’s collection helps preserve their ambitions, their engineering, their inventions, their successes, and their failures. The earliest of these stories begins with a car built at a moment when the automobile industry was still an open frontier—the 1907 Reliable Dayton Surrey.

1907 Reliable Dayton Surrey: Buck Harness’s Brass‑Era Time Capsule

A Car Born in a Transforming America

The Reliable Dayton Surrey emerged during one of the most experimental periods in American automotive history. Between 1900 and 1910, more than a thousand small manufacturers tried their hand at building automobiles. Roads were mostly unpaved, horses still dominated transportation, and no single design standard had yet taken hold. High‑wheelers—cars with tall, wagon‑like wheels—were especially popular in rural areas because they could handle mud, ruts, and uneven terrain far better than the low‑slung cars that would come later.

It was in this landscape of invention, optimism, and fierce competition that William Dayton introduced the Reliable Dayton.

William Dayton’s Path into Automaking

William O. Dayton did not enter the automobile business blindly. Before the Reliable Dayton appeared in 1906, he operated the Dayton & Mashey Automobile Works in Chicago, a plant that built engines and allowed him to experiment with mechanical designs. This work gave him both the technical foundation and the financial footing to launch his own automobile line.

A High‑Wheeler Built for Rural America

In the spring of 1906, the Reliable Dayton high‑wheeler Model C was officially introduced. It was a sturdy automobile designed for America’s rough rural roads. The car used a rope drive and a water‑cooled twin‑cylinder engine tucked under the seat, rated at 15 horsepower. A fin‑tube radiator sat above the front axle, giving the car a distinctive, carriage‑like profile.

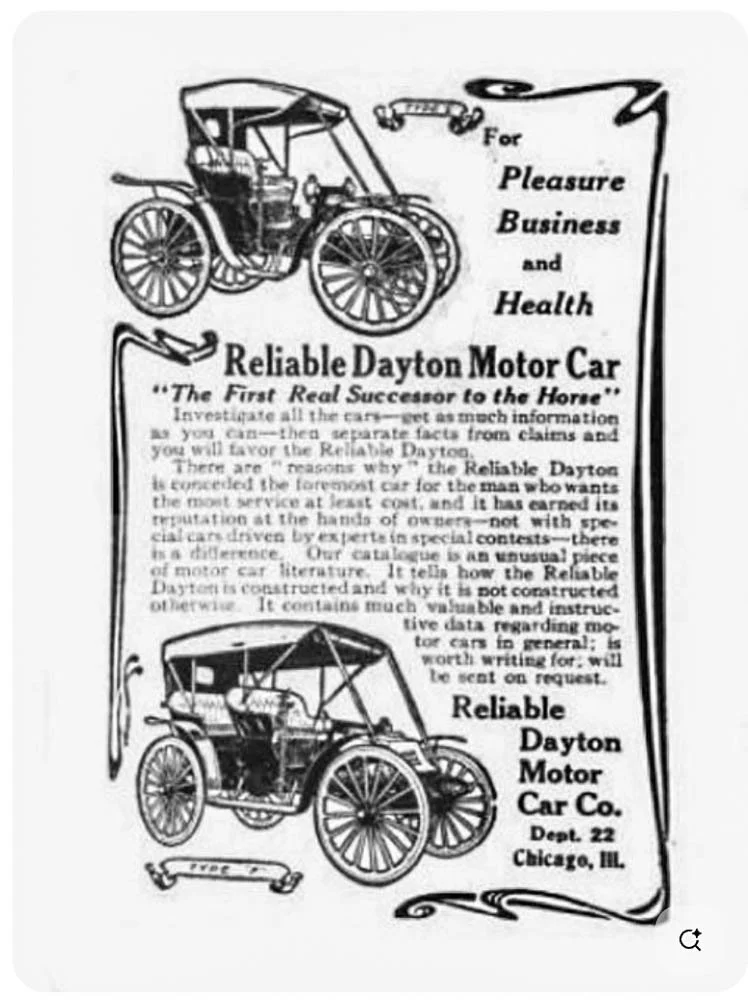

The company promoted its cars as “The First Real Successor to the Horse.” Choosing the name “Reliable” was a bold marketing move. As one historian noted, “One way to advertise, and make a bold statement, was to give the vehicle a daring name.” In an era when automobiles were still viewed as temperamental machines, the promise of reliability was exactly what buyers wanted to believe.

Models, Prices, and Intended Buyers

Reliable Dayton Motor Car

The First Real Successor to the Horse

Reliable Dayton offered three body styles:

Surrey – open‑air, two bench seats

Runabout – open‑air, single bench seat

Coupe – enclosed, single bench seat

Prices ranged from $780 for the Runabout to $925 for the Surrey, and up to $1,200 for the Coupe—significant sums at the time. These cars were marketed to farmers and small‑town professionals who needed dependable transportation across muddy, rutted roads. Tall wheels and solid rubber tires made them practical choices for rural America.

How Buck Found His Surrey

Buck Harness first saw his 1907 Reliable Dayton Surrey in an ad in Hemmings Motor News. A museum in Pennsylvania was closing and selling its collection of old cars. The Reliable Dayton had been stored for fifty years and needed a new home. Buck remembered how complete the car appeared—the body was mostly intact, and the wheels were still present—but it was far from roadworthy. The engine was silent and refused to start.

Restoring a Forgotten Machine

After bringing the car home, Buck began the meticulous restoration process. He crafted missing fenders, installed period‑appropriate lamps, and tracked down or fabricated mechanical parts that were missing or damaged. He restored the top, replaced the headliner, and added bright yellow fringe to match the wheels. After considerable work, the Surrey’s two‑cylinder engine finally sputtered back to life.

Buck later admitted that driving the car was unnerving. “It was scary to drive,” he said, describing the high stance and primitive controls that made every trip feel both exciting and risky.

A Short‑Lived Company in a Fast‑Changing Industry

By 1909, the Reliable Dayton faced overwhelming competition. Larger manufacturers were producing more refined vehicles, and the high‑wheeler design became obsolete. That year, the company’s factory was taken over by the Fal Motor Company, which produced F.A.L. automobiles until 1914. William Dayton moved on to other ventures.

Why the Reliable Dayton Still Matters

Though short‑lived, the Reliable Dayton remains an important chapter in America’s Brass Era. Its name captured the hopes of early motorists. Its design reflected the transition from horse‑drawn carriages to modern automobiles. And through collectors like Buck Harness, the brand’s story continues to be preserved and shared.

The Reliable Dayton may have been Buck’s most challenging high‑wheeler, but it was far from the only early automobile he brought back to life.

1909 Rauch & Lang Electric: Buck Harness’s Silent Carriage

A Car That Looks Backward but Moves Forward

People stop and stare when Buck Harness brings out his 1909 Rauch & Lang Electric. At first glance, it appears to be a beautifully preserved horse‑drawn buggy from the 1880s or 1890s—single bench seat, collapsible soft top, and narrow wooden wheels. It looks ready for a team of horses. But when Buck eases it forward, there is no clatter of hooves, no scent of manure, and no swish of a whip. Only the faint hum of an electric motor breaks the silence.

From Carriage Makers to Electric Innovators

The Rauch family’s story in Cleveland began in 1853, when Jacob Rauch, a German blacksmith, opened a small wagon‑repair and carriage shop on Pearl Street. Over the next several years, the business grew steadily, and Jacob’s son, Charles Rauch, joined him in the trade. By the 1870s, Charles was taking on more of the day‑to‑day carriage building as the business expanded.

The partnership that created the company we now know as Rauch & Lang did not form until 1878, when Charles E. J. Lang, a Cleveland businessman and real‑estate promoter, purchased a one‑quarter interest in the Rauch family carriage works. Lang brought capital, business connections, and ambition; Charles Rauch brought craftsmanship and a well‑established carriage operation. Together, they reorganized and incorporated the business as the Rauch & Lang Carriage Company in 1884.

By the early 1900s, the “horseless carriage” was quickly gaining popularity. Demand was high. Charles Rauch and Charles Lang saw opportunity not in gasoline or steam, but in electricity—an emerging force that was beginning to light homes, power streetcars, and reshape daily life. In 1903, the company entered the automobile industry.

The Rise of the Electric Stanhope

In 1905, the company introduced its first electric Stanhope, a body style originally created nearly a century earlier by London coachbuilder Captain Fitzroy Stanhope. Rauch & Lang adapted the design for the electric age. Production grew quickly: 500 vehicles in 1908, more than 1,200 in 1909. Their cars became symbols of refinement, often driven by fashionable women who appreciated their quiet operation and ease of control.

Competition and Decline

The electric car’s early promise was short‑lived. Gasoline automobiles offered longer range, faster speeds, and rapidly expanding infrastructure. In 1919, Rauch & Lang merged with the Baker Motor Vehicle Company, another electric car manufacturer. A year later, the passenger car division was sold to Stevens‑Duryea in Massachusetts and reorganized as Rauch & Lang, Inc.

The company shifted to building taxicabs—both electric and gasoline—but the electric models struggled. By the mid‑1920s, passenger electrics had nearly vanished. By 1932, the Rauch & Lang name disappeared from the automotive landscape.

What Made the Rauch & Lang a Luxury Electric

Although Rauch & Lang cars looked like elegant carriages, their engineering was thoroughly modern for 1909. Most models of the period used a compound‑wound electric motor, influenced by designs from Hertner Electric, which the company acquired in 1907. Power came from Exide lead‑acid batteries, widely advertised at the time as “rugged” and “of enormous capacity.” Power was delivered to the rear wheels through a double‑chain drive, and drivers controlled the car with a multi‑speed electric controller that offered several forward and reverse speeds. Steering was by tiller, and braking was electric, as well.

Top speed was generally between 16 and 20 miles per hour—more than adequate for city streets—and the cars were known for strong, low‑speed torque, a natural advantage of electric motors. Depending on conditions, a full charge allowed the car to travel 40 to 60 miles. Tires were either Palmer web pneumatic or Motz cushion types, both designed to withstand the weight of electric vehicles. Luxury touches rounded out the design: electric lighting, Corbin key locks for the controller, satin ceilings, and window shades on enclosed models. For their time, Rauch & Lang electrics were among the most refined vehicles on the road.

How Buck Found His Electric Car

Decades later, Buck Harness found his Rauch & Lang in Gas City, Kansas, about 125 miles southwest of Clinton. The car had survived, but not gracefully. “The wood just rotted off of it,” Buck recalled. Fortunately, the original owner’s manual came with the car. “From it I could build the body,” he once wrote—and he did.

The wheels came from Indiana. The fender material came from the Amish in Pennsylvania. “They used it on their buggies,” Buck explained. The top bows were also Amish‑made. When asked what the most difficult part of the restoration was, he answered without hesitation: “I suppose the wheels and the upholstery were the most challenging part.”

A Motor That Needed Little More Than Dusting

The electric motor, however, was a pleasant surprise. “It apparently was a low‑mileage car because the motor was like new,” Buck said. “I didn’t have to do anything except clean the cobwebs off of it.”

He sourced modern batteries from a local golf cart company. When asked about the range, he chuckled: “It will go from here to the Clinton Square and back—about sixteen blocks round trip.” In its day, the car used Exide batteries, the leading brand for automobiles, streetcars, and even submarines. Edison batteries were optional. A fully charged original battery pack could carry the car roughly 60 miles. Buck never found an original Exide battery, but he did locate an original battery charger in Pebble Beach, California.

Buck’s Favorite Car

More than a century after it was built, his Rauch & Lang still turns heads—and still moves quietly down the road, just as its makers intended. When asked which car in his collection he likes best, Buck doesn’t hesitate. “The electric one. I don’t have to crank it. I don’t have to put oil in it, or anything.”

Buck’s restored 1909 Rauch & Lang Electric tells the story of a company that began with carriages in the 1850s, rose to prominence as a luxury electric automaker, and faded as gasoline cars took over. It also tells the story of a man who still values the simple pleasure of driving an electric buggy. “You don’t have to crank it,” Buck says again, smiling.

1912 American Underslung Tourist: A Low‑Slung Legend and a Twenty‑Year Restoration

A Company Built on Ambition

In 1905, a group of Indianapolis businessmen formed the American Motor Car Company with the goal of producing high‑quality American touring cars. In its earliest months, the company existed mostly on paper—sketches, discussion papers, and formal plans—before production finally began.

The first model rolled off the line in 1906. Designed by Harry Stutz, a gifted young engineer who would later become famous for the Stutz Bearcat, the car was a conventional high‑frame touring model. It was well‑designed and competitive for its time. But Stutz left the company shortly after production began, opening the door for a new engineer with a very different vision.

Fred Tone’s Radical Idea

Stutz’s departure brought Fred Tone to the forefront. Formerly the chief engineer at the Marion Motor Car Company, Tone was given a clear mandate: design a car unlike anything else on the road.

His breakthrough came from a simple observation. Watching chassis frames being unloaded upside‑down, he wondered what would happen if a car were built that way on purpose. What if the frame sat below the axles instead of above them?

The result was the underslung chassis—a radical departure from conventional automotive design. By placing the frame low and mounting the suspension springs above it, Tone created a car with a dramatically lower center of gravity, a long, sweeping stance, enhanced stability, and a distinctive ground‑hugging look. The company promoted the idea that its unique design wasn’t top‑heavy. In their words, the Underslung “wouldn’t turn turtle” like an ordinary automobile.

When the first American Underslung models appeared around 1907, they immediately stood out. No other American car looked like them.

The 1912 Lineup: Built for the “Discriminating Few”

By 1912, American had abandoned its traditional high‑frame cars and settled into a three‑model lineup showcasing the underslung design in three different sizes and price ranges:

Traveler – a large, top‑tier touring car

Tourist – a mid‑range touring model

Scout – a smaller, nimbler, sportier roadster

Prices ranged from $1,250 to $4,000, placing them among the most expensive American‑made cars of the era.

The Tourist name had been used before, but the 1912 Tourist was entirely new: fully underslung, built on a 118‑inch wheelbase, and priced at $2,250—roughly $75,000 today. It carried the same low stance and elegant proportions as the larger Traveler, but in a slightly more accessible package.

The company marketed the lineup as “The Car for the Discriminating Few.” Unfortunately, too few discriminating buyers were willing to pay the price. With high manufacturing costs and slow sales, the company entered receivership in late 1913. Production stopped the following year.

The American Underslung disappeared from the market, but its reputation as an engineering marvel was only beginning.

Technical Specifications of the 1912 American Underslung Tourist

The 1912 Tourist didn’t just look dramatic with its low, sweeping stance—it was built to be a strong, capable touring car. It rode on a long 118‑inch wheelbase and weighed about 2,550 pounds, giving it a solid, confident feel on the road. Its four‑cylinder engine was large for the era and delivered enough power to move the car smoothly over the rough, unpaved roads of the time. The Tourist used high‑quality components throughout, including a dependable magneto ignition system and a well‑tuned carburetor that kept the engine running cleanly.

Power reached the rear wheels through a three‑speed transmission, and the car’s suspension—leaf springs mounted above the axles—created the famous underslung look while keeping the ride surprisingly stable. Steering was handled through a sturdy gear system, and braking came from rear drum brakes, which were standard for the period. The tall wheels and narrow tires helped the car maintain ground clearance despite its unusually low frame.

Altogether, the Tourist combined style, comfort, and solid engineering. It offered buyers a refined, premium automobile that stood out from the average car on the road, both in appearance and in the way it drove.

A Forgotten Body Shell and the Beginning of a Hunt

Many decades later, one forgotten American Underslung found an unlikely steward. Buck Harness, a fireman with a passion for early automobiles, began his journey not with a complete car, but with a mystery.

He first discovered the body—just the body—sitting on a friend’s property. “I didn’t know what I was going to do with it,” he remembered, “but I had to have it.” He paid $200 for the shell, not yet knowing what it was. Only after researching the unusual shape did he realize he had found something rare: the body of a 1912 American Underslung Tourist.

Once he knew what he had, the hunt began.

A Thousand Miles for a Chassis

“I took a 1000‑mile trip and bought the chassis,” he said. “But it didn’t have an engine in it.” A year later, at a swap meet, he spotted a motor with “American 30” written across the top. “And I bought the engine.”

Piece by piece, he rebuilt the car. Some parts he found by luck, others by instinct. He located the chassis in Northern California. The fenders and parking lamps were in Oklahoma. “They didn’t know what these parts fit,” he said of swap meet sellers. “And I did. So I got them at a reasonable price.”

Rebuilding a Legend

The hood was built from scratch, using period photographs and accurate measurements to ensure precision. Amish wheelwrights in Pennsylvania made the 29-inch tall wheels. He found authentic seats in surprisingly good condition and upholstered the side panels himself. The rear lamp, originally kerosene‑lit, was later wired for safety.

On the bumper of the finished car, he placed a handwritten placard:

1912 American Underslung “Tourist”

Engine: 4 cyl. 4‑1/2” x 5” 30 H.P.

Ignition: Bosch Magneto

Tires: 34x4 – 29”

Frame: Underslung – Springs on Top

Original Price: $2,250

ONE OF THREE

Owner: Buck Harness, Clinton, MO

A Rare Survivor

The American Motor Car Company lasted less than a decade, but its underslung design became legendary. Today, surviving examples are exceedingly rare. Buck’s restored 1912 American Underslung Tourist—rebuilt piece by piece over twenty years—is one of three known to exist.

It stands as a testament to the ingenuity of early American engineering and to the persistence of a man who saw a forgotten body shell in the weeds and recognized a piece of history waiting to be saved.

The next car in Buck’s barn could not be more different: a lightweight, open‑air machine built for speed and simplicity—the 1915 Ford Model T Speedster.

1915 Ford Model T Speedster: A Grassroots Racer Built by Everyday Americans

A Racing Car Ford Never Built

Contrary to popular belief, the Ford Model T Speedster was never factory‑produced. Although Ford briefly experimented with racing—most notably with Frank Kulick driving Ford “Special” racers in events like the 1911 Algonquin Hill Climb—Henry Ford quickly stepped away from factory competition. He believed racing distracted from his mission of providing basic, affordable transportation. When he introduced the Model T in 1908, it was intended to be “the car for the masses”—durable, practical, and inexpensive. Millions were sold.

A Platform for Creativity

Model Ts soon appeared everywhere: in towns and cities, on farms and dirt roads, in parades, and in daily work. Their commonality made them the perfect platform for experimentation. By the early 1910s, driven by a love of speed and a sense of adventure, ordinary Americans began transforming their stock Model Ts into custom speedsters.

Enthusiasts removed the heavy touring bodies and replaced them with lightweight shells and bucket seats. Aftermarket suppliers offered performance upgrades—high‑compression heads, improved carburetors, and even overhead‑valve conversions. The results were impressive for the era. While a stock Model T topped out around 42 mph, stripped‑down and modified speedsters could reach 50–60 mph.

These homemade machines competed in hill climbs, endurance runs, and dirt‑track races. As one historian observed, “Speedsters offered ordinary drivers an affordable way to experience the thrill of racing.”

Buck’s Speedster and the Racing Tradition

Buck Harness’s 1915 Speedster fits squarely into this grassroots racing tradition. At some point in its life, the car was stripped down to its chassis and rebuilt into the form it has today. Buck recalled that the fenders “are all reproductions, but they are exactly like the originals.” The leather strap over the hood wasn’t decorative—it was practical. Without it, the hood could fly open at high speeds. “The hood could just pop open,” Buck remembered.

A Symbol of Early American Motoring

The Model T Speedster represents the creative, playful side of early American motoring. Ford never officially sold a speedster, but enthusiasts across the country built their own. These cars helped ignite a grassroots racing movement that shaped the future of hot rodding and amateur motorsports.

Thanks to Buck Harness’s dedication and generosity, his 1915 Model T Speedster will soon be displayed permanently at the Henry County Museum. Visitors will be able to see, up close, a vivid reminder of an era when everyday people transformed mass‑market cars into racing dreams.

Buck’s Speedster captures the thrill of early American racing, but the next car in his barn served a very different purpose—a sturdy, work‑ready machine built for hauling and hard labor: the 1918 Autocar.

1918 Autocar: A Workhorse Built for Anything

A Company Rooted in Engineering Ingenuity

Mechanical engineer Louis Semple Clarke, known simply as L.S., founded the Pittsburgh Motor Vehicle Company in 1897. That same year, Clarke and his family built the company’s first vehicle, Autocar No. 1, a one-cylinder, gasoline-powered tricycle now displayed at the Smithsonian Institution. In 1898, they followed with Autocar No. 2, a four-wheeled runabout called the Pittsburgher, which is now at the Henry Ford Museum.

By 1899, the company was already breaking new ground. That year, it produced a “motor truck,” the first commercially designed delivery wagon in the United States, capable of hauling a 700‑pound payload. Its “engine‑under‑the‑seat” layout foreshadowed the cab‑over‑engine design that would define Autocar trucks for decades. In the same year, the company relocated to Ardmore, Pennsylvania, and adopted the name Autocar.

Turning Toward Trucks

As the automobile industry became crowded with passenger cars, Autocar saw a different opportunity. Factories, farms, and municipalities needed machines that were sturdier and more reliable than regular automobiles. By the early 1900s, Autocar made a decisive shift, abandoning passenger cars to focus entirely on purpose-built commercial trucks.

Autocar specialized in building complete rolling chassis—a fully engineered mechanical foundation that included the engine, transmission, driveshaft, axles, suspension, steering mechanism, wheels, tires, radiator, controls, and fuel system. In short, everything needed to operate the machine except the body. This approach enabled a wide range of customers and coachbuilders to create the exact vehicle they wanted, such as a produce hauler, a dump truck, a taxi, or a passenger wagon.

The 1918 Autocar in Context

Buck Harness’s 1918 Autocar emerged during a period of industrial expansion and wartime demand. Its reputation for reliability made it a favorite for taxis, delivery wagons, and municipal vehicles. As Buck recalled, “This one was used to haul people. I have pictures of them where they used them for dump trucks…all kinds of stuff.”

Buck’s restoration of his 1918 Autocar reflects that tradition of adaptability. He salvaged wood from a neighbor’s church project to rebuild the roof. His craftsmanship echoes Autocar’s original philosophy: build a rugged platform and let the owner shape it to their needs.

Clarke’s Lasting Influence

Clarke’s legacy is built not on a single invention but on how he helped shape the fundamentals of American automotive engineering. He experimented with spark plug designs for gasoline engines, improved lubrication systems by introducing circulating oil, and promoted the use of drive shafts over chains. These improvements and others gave Autocar vehicles greater durability and efficiency. While others later popularized these ideas, Clarke’s early adoption showed a clear vision of how automobiles should serve the people who used them.

Taken together, Clarke’s contributions established Autocar’s reputation for engineering precision and practical design. His influence is embedded in Buck’s 1918 Autocar: a machine built for reliability, versatility, and everyday use in moving people and goods.

A Legacy That Endures

Autocar’s independence ended when White Motor Company acquired it in 1953. It later became part of Volvo White Truck Corporation in 1981. In 2003, operations moved to Hagerstown, Indiana, and in 2014 Autocar was purchased by GVW Group LLC. Today, it continues to build severe‑duty commercial trucks.

Autocar is the oldest continuously operating motor vehicle brand in the United States. Though it passed through several owners, its legacy remains intact. Clarke’s innovations—and the company’s reputation for rugged, customizable workhorses—live on.

Buck’s 1918 Autocar, restored with care and resourcefulness, represents Autocar’s legacy perfectly: a machine built to do whatever its owner needed, and a reminder of how American ingenuity shaped the vehicles that carried a nation forward.

Moving from the 1918 Autocar to the next vehicle in Buck’s barn shifts the story from commercial utility to personal transportation. The Autocar was a multipurpose workhorse. In contrast, the 1921 Ford Model T Coupe marks the point when automobiles became everyday cars designed for daily life.

1921 Ford Model T Coupe: A Practical Classic with a Personal Touch

Henry Ford’s Early Struggles and Clear Vision

Henry Ford’s story began a century before Buck Harness ever laid eyes on his 1921 Model T Coupe. Ford was a young mechanic in Detroit, experimenting with gasoline engines when he built his first motorized vehicle, the Quadricycle, in 1896. It was little more than a frame with four bicycle wheels and a small engine, but it worked. It proved his ideas had promise.

Ford’s first two companies failed. The Detroit Automobile Company collapsed in 1899 because its cars were too expensive and poorly made. His second venture ended in 1901 due to disagreements with investors who sought to build luxury cars, whereas Ford sought to build affordable ones.

But these were “good failures.” Ford walked away with something more valuable than profit: a reputation as a gifted engineer with a clear vision—build cars ordinary people could afford.

The Turning Point

Ford’s breakthrough came on October 10, 1901, when he won a sweepstakes race at the Grosse Pointe Race Track. That victory attracted the attention of John and Horace Dodge, who invested capital, machining expertise, and manufacturing capacity. Their support gave Ford credibility within Detroit’s industrial circles.

Automobiles were the new frontier in 1903, much like the tech and AI boom of today. Investors were eager to back promising ventures. With the Dodge brothers’ help, Ford assembled twelve investors who contributed $28,000—over a million dollars today. They weren’t betting on Ford as a businessman; they were betting on his engineering skill and his commitment to affordable cars.

On June 16, 1903, Ford Motor Company was incorporated. Within a month, the company received its first order for the new Model A.

From Model A to Model T

Ford labeled his designs alphabetically—Model A, Model B, and so on—each representing another step in his engineering progress. By 1908, he had reached the twentieth letter of the alphabet. The car introduced that year became the Model T. The name wasn’t symbolic; it was simply next in sequence. But the Model T would become the car that transformed America.

The 1908 Model T was exactly what Ford had envisioned: durable, simple, and affordable. By 1913, Ford perfected the moving assembly line, reducing production time from twelve hours to ninety minutes. Costs fell, output soared, and millions of Americans gained access to personal transportation.

The 1921 Coupe: A Professional’s Car

Among the many variations of the Model T was the 1921 Coupe, often nicknamed the “Doctor’s Coupe.” Ford never used the name officially, but the enclosed body style appealed to professionals who wanted protection from the weather and a touch of refinement.

The 1921 Coupe featured a wood‑framed cab, comfortable seating, and reverse‑hinged doors—later called “suicide doors” due to the risks they posed if opened while moving. It was also one of the first Model Ts equipped with an electric starter, though the hand crank remained as a backup. The car had two forward speeds, which some owners found limiting compared to three. More than 327,000 Coupes were built in 1921–22, making them distinctive but not especially rare.

Buck Finds His Coupe

Buck Harness found his 1921 Coupe at a swap meet in Los Angeles. He remembered two stalls: one selling a pile of Model T parts for $1,000, the other offering a complete car for the same price. “I bought the real car,” he said with a grin.

The Coupe’s wood was rotten at the bottom of the doors, but Buck saw potential. He tore it down to “the last nut, bolt, and screw,” rebuilt the engine, replaced the fenders and running boards, restored the cab—including the rotted doors—and painted the car by hand. He upholstered it himself using a modification kit. “It’s very soft to sit in,” Buck said. “You sit up high.”

A Personal Restoration

Buck added wire wheels, a tinted glass sun visor, and side mirrors for safety—practical additions not original to the car. Inside, he placed a small flower vase gifted by a woman who had saved it since childhood. It was a simple touch, but it gave the Coupe a bit of personality.

For Buck, the joy was in the work itself. “Just something to work on,” he laughed. The two‑speed transmission frustrated him, as he believed three gears would be better, but the satisfaction of bringing the car back to life outweighed its flaws.

A Legacy Carried Forward

From Henry Ford’s Quadricycle to Buck Harness’s 1921 Coupe, the story of Ford is both industrial and personal. Ford Motor Company revolutionized manufacturing and transportation, becoming one of the largest and longest‑lasting automobile makers in the world. And Buck Harness carried that legacy forward—one bolt, one fender, and one flower vase at a time.

The next car in Buck’s barn takes us in a different direction—a machine built for power and endurance rather than refinement: the 1924 Stanley Steamer.

1924 Stanley Steamer: The Photographers Who Built a Car

From Portrait Studio to Engineering Workshop

Before the Stanley Steamer ever pressurized a boiler, Francis Edgar Stanley and Freelan Oscar Stanley were already well known for a very different kind of technology. Their story began in a portrait studio in Lewiston, Maine, where Francis launched a photography business in 1874. The studio grew rapidly, becoming one of the most respected in New England. Freelan soon joined him, and together the twins built a reputation for artistry, precision, and inventive skills.

Francis, frustrated with the limitations of existing tools, patented an early photographic airbrush that allowed him to retouch and colorize images with unmatched precision. That same inventive spirit led the brothers into the rapidly expanding field of dry‑plate photography. Their Stanley Dry Plate Company soon produced plates of exceptional consistency and quality. By the 1890s, the business earned more than $1 million a year, or roughly $39 million today.

A New Obsession: Steam Power

Even as their photography business thrived, another technology captured their imagination. In the back rooms of their factory and in their home workshops, the brothers began sketching, machining, and assembling parts for a steam‑powered vehicle.

Their first automobile appeared in 1897, built during the same years they shipped dry plates across the country. For a time, the two worlds ran in parallel: photography by day, steam engineering at night.

The Stanleys were both engineers and showmen. In 1899, Freelan and his wife, Flora, drove a Stanley car to the summit of the 7.6‑mile Mount Washington Carriage Road—the first automobile to do so. The feat cemented the Steamer’s reputation for power and reliability. By year’s end, the brothers had sold more than 200 vehicles, more than any other U.S. automaker at the time. Steam cars seemed poised to dominate the future.

Confident in their prospects, the brothers formally founded the Stanley Motor Carriage Company in 1902.

Leaving Photography Behind

In 1904, George Eastman of Eastman Kodak offered the Stanleys $500,000—roughly $17 million today—for their dry‑plate operation. The decision was easy. Photography had made them wealthy, but automobiles offered something more: the chance to help build an entirely new industry.

Freed from the demands of their photographic empire, the Stanleys devoted themselves fully to steam‑car engineering. Their names soon became fixtures in early American automotive history.

Speed, Smoothness, and Myth

By the early 1900s, Stanley Steamers were known for their speed and smoothness. In 1907, at Ormond Beach in Florida—later called the “Birthplace of Speed”—a Stanley racer nicknamed “The Flying Teapot” reached nearly 200 mph before hitting a bump, lifting off, and crashing hard. The driver survived, but the incident fueled myths about boiler explosions, even though the accident was caused by speed, not steam.

Stanley cars featured wooden bodies, kerosene‑fired boilers, and whisper‑quiet engines. They were luxurious yet quirky, with an unmistakable mystique. Owners and restorers often described them with a mix of admiration and caution. Buck Harness captured that feeling perfectly when he said, “This is about the last model they made…” When asked if he ever started it, he admitted, “No, it was just spooky… afraid it would blow up on me.”

The Ritual of Steam

Starting a Stanley Steamer required ritual-like preparation. Buck Harness’s handwritten guide, “To Start Stanley Steamer,” shows the complexity of filling tanks, pressurizing air, lighting pilots, and waiting for steam pressure to build. He ended the instructions with a wry note: “THE END – MAYBE.” His humor reflected the wider public’s unease with steam power.

Yet the fear was largely unfounded. The Stanley Museum, the Stanley Steam Car Club, and other engineering historians have found no record of a Stanley boiler explosion causing death or serious injury. Over 10,000 cars were built and driven tens of millions of miles, often under harsh conditions. The reason for their safety lies in their design:

· Piano-wire-wound boilers designed to leak rather than explode

· Multiple safety valves to prevent over‑pressure

· A fusible plug that melted at high temperatures to relieve pressure

· An automatic burner shutoff if the pressure rises too high

In their time, Stanley boilers were among the safest pressure vessels in use for any purpose.

Buck’s Steamer: A Wooden Skiff on Wheels

Buck rebuilt his 1924 Stanley Steamer with careful dedication, saying he rebuilt “all of it. The whole thing… just pulled it out of my head.” His craftsmanship shows in every detail. The red and green sidelights he added were “like a boat,” reflecting the nautical theme of the “Skiff” body style first imagined by French designer Henri Labourdette for yachtsmen who wanted a car that moved as gracefully on land as their vessels did on water.

The End of the Steam Era

By the 1910s, gasoline-powered cars had become cheaper, easier to start, and far simpler to maintain. The Stanley company struggled to adapt. Francis Stanley died in 1918, and by 1924, the firm was dissolved, overwhelmed by the rapid rise of gasoline technology.

Still, the Steamer remains legendary.

Buck’s restored 1924 model, with its handcrafted wood, intricate boilers, valves, and fittings, stands as a living historical artifact of an era when steam seemed destined to dominate the roads. The Stanley Steamer was born from the ingenuity of twin brothers who built cars that whispered rather than roared, outperformed rivals in their prime, and demanded ritual and respect from their drivers. By the mid‑1920s, however, steam gave way to gasoline, and the age of the Steamer came to a close.

The Stanley Steamer marked the end of an era, an elegant machine powered by heat and pressure, and built by two inventive brothers who believed steam had a future. The next car in Buck’s barn comes from a very different tradition: a low‑slung, gasoline‑fueled symbol of speed and American swagger—the 1928 Stutz Bearcat.

1928 Stutz Bearcat: The Last Roar of an American Legend

A Farm Boy with a Mechanical Imagination

Harry Clayton Stutz began life far from the roar of racetracks or the glamour of luxury automobiles. Born in 1876 on an Ohio farm, he built his first gasoline‑powered vehicle in 1898 from scrap and stubborn curiosity. That homemade machine set him on a path that would eventually reshape American performance motoring.

By the early 1900s, Stutz had made his way to Indianapolis, where he became chief engineer and designer of the first car produced by the American Motor Car Company. It was his first opportunity to design a complete automobile, and he poured himself into it. The experience sharpened his engineering instincts and gave him credibility in a young industry hungry for innovation.

The Stutz—Tone Job Swap

In one of those moments that shows just how small and interconnected the early Indianapolis auto world was, Harry Stutz and Fred Tone essentially switched places. Tone had been chief engineer at the Marion Motor Car Company, while Stutz was chief engineer at American. Around 1906, both men left their posts in search of better opportunities—and each ended up taking the other’s former job. Tone went to American, where he soon developed the famous American Underslung chassis. Stutz went to Marion, where he became chief engineer and factory manager.

Marion proved to be a turning point. It was there that Stutz designed the Marion Bobcat speedsters, light, lively roadsters built for drivers who wanted something raw and responsive. The name “Bobcat” fit the car’s character: small, quick, and aggressive. It also established a naming pattern that Stutz would later echo.

Marion gave Harry more than a job title. It gave him racing experience, exposure to high‑performance engineering, and a chance to refine the ideas that would define his later work: durability, simplicity, and a direct mechanical connection between driver and machine. It was the final apprenticeship before he stepped onto the national stage.

Ready for Independence

By 1911, he was ready to build something of his own. He founded the Ideal Motor Car Company, built a car in less than five weeks, and entered it in the inaugural Indianapolis 500. The car finished 11th, without a single test lap. That astonishing debut launched the Stutz Motor Car Company and gave birth to a slogan that would follow the brand for decades: “The car that made good in a day.”

From that moment, Stutz was not just a company. It was a statement.

The Birth of the Bearcat

By 1912, the Stutz Motor Car Company had found its identity. The car that had stunned Indianapolis the year before was now in full production. Harry named the performance roadster he created—the car that stunned the Indianapolis 500—the Stutz Bearcat. The shift from Bobcat to Bearcat wasn’t accidental. It suggested something larger, stronger, and more formidable, a natural evolution from the nimble Marion speedsters to the bolder, more powerful Stutz machines. The Stutz Bearcat quickly became a symbol of wealth and adventure.

The Bearcat was built in the image of its founder: straightforward and unpretentious. It looked fast because it was fast. Little more than an engine, a frame, two bucket seats, and a fuel tank, the Bearcat was a roadster for people who wanted to feel the road rather than glide over it. They wanted to hear the engine and feel its power in their chest.

Racing Success and Engineering Innovation

The Bearcat became one of the most recognizable performance cars in America. The company’s “White Squadron” racing team won national championships in 1913 and 1915. These victories mattered. In an era when racing results sold cars, Stutz’s performance directly enhanced its prestige, and sales soared.

Stutz also developed innovations that set it apart. Early Bearcats featured a four‑valve‑per‑cylinder T‑head engine, one of the earliest multi‑valve performance engines in American production. Harry Stutz’s earlier work on transaxle design influenced the company’s approach to drivetrain layout and handling. Stutz cars were known for stability, responsiveness, and durability under punishing conditions.

Losing Control of His Own Company

Success brought complications. In 1916, financier Allan Ryan gained control of the company through a stock battle that left Harry Stutz increasingly sidelined. By 1919, after years of financial maneuvering, Harry walked away from the company he had built.

At 43, he was not ready to retire. He immediately founded the H.C.S. Motor Car Company and soon after established the Stutz Fire Apparatus Company, designing fire engines, pumpers, and ladder trucks. But his departure marked the end of the original Bearcat era as he had envisioned it.

The Final Bearcat

Even so, the Bearcat name endured into the 1920s. And in 1928—the final year the Bearcat name appeared on a Stutz automobile—a car was built that would one day find its way to a car collector’s barn in Clinton, Missouri.

Today, nearly a century after it was manufactured, Buck Harness stands beside that very car: a 1928 Stutz Bearcat. The last of its kind. He found it as a bare chassis—the bones of a legend. The body he sourced from California was rare, a survivor from the era when coach builders shaped cars with artistry and heart.

Buck rebuilt it piece by piece, upholstering it himself and tracking down the small details that made Stutz famous. When he opens the restored rumble seat, it feels like opening a door to the 1920s. His Bearcat is the final chapter of the Bearcat story, built just before the name was retired and replaced by the Blackhawk the following year.

The End of an Era

By the late 1920s, Stutz leadership knew the Bearcat’s era was ending. The raw, open‑bodied, two‑seat roadster belonged to an earlier generation. Wealthy buyers now wanted refinement, with enclosed bodies and comfort.

In 1929, Stutz introduced the Blackhawk, a new model line with modern styling and a more refined driving experience. It was not an evolution of the Bearcat; it was a replacement. The timing could not have been worse. The Great Depression struck just as the Blackhawk debuted. Luxury automakers suffered first and hardest. Stutz’s cars were expensive, exclusive, and suddenly out of step with a nation tightening its belt. Production collapsed. Losses mounted. By 1936, only six Stutz cars were built, and the company closed its doors.

Harry Stutz did not live to see the final unraveling. He died in 1930 at age 53, from complications following an operation for appendicitis.

A Legend Preserved in Clinton, Missouri

Today, the Stutz Motor Car Company survives through the devotion of people like Buck Harness. He doesn’t talk about engineering theory or corporate history or famous automobile personalities. He talks about the Stutz body he found in California. The upholstery he stitched himself. The rumble seat he restored. The details that matter most.

His Bearcat is a bridge between a young engineer designing his first car in Indianapolis, a daring founder proving his machine at the first Indy 500, a company that became a legend, and a quiet, self‑taught craftsman in Clinton, Missouri, who keeps the Stutz Bearcat story alive.

The company is gone, but the legend lives on. And Buck, in his quiet way, carries its history forward—not through words, but through the joy of work.

The Stutz Bearcat was the last roar of a fading performance era. It was a car built for speed and open-air bravado. The next vehicle in Buck’s barn comes from a different world entirely, one shaped not by racing glory but by practicality, reliability, and the needs of a nation on the move: the 1929 Ford Model A.

1929 Ford Model A: Reinvention for a New Era

From Model T to Model A

Henry Ford finally retired the Model T in 1927 after eighteen years of production. The decision was far overdue. Ford’s market share had fallen from 55 percent in 1921 to just under 10 percent by 1927. The Model T had “put America on wheels,” but competitors now offered sleeker designs, better performance, more comfort, and more options. Customers, presented with more choice, were leaving Ford behind. It was time for something new.

Ford’s answer was the Model A—a name traced to the company’s origins but offering a fresh perspective.

A Modern Ford for a Modern America

Unlike the sparsely appointed Model T, the Model A introduced in December 1927 represented a major leap forward. It featured a 200.5‑cubic‑inch, 40‑horsepower engine, a three‑speed manual transmission, four‑wheel drum brakes, and hydraulic shock absorbers. It could accelerate from 0 to 60 mph in under twenty‑five seconds and delivered 25 to 30 miles per gallon.

The Model A came in dozens of body styles, from roadsters to sedans, with options such as wire wheels and a rumble seat. It also came in multiple colors—a clear departure from the Model T’s famous motto, “any color so long as it’s black.”

Nationwide advertising brought more than ten million visitors to dealer showrooms in the first week alone. By February 1929, Ford had sold one million Model As; by July, two million. It was a runaway success and proof that Ford could reinvent itself.

A Car for Hard Times

The Model A’s timing was both fortunate and challenging. When the stock market crashed in October 1929, Ford’s new car was already firmly established. Its affordability helped families weather the Depression years, and historians noted that the Model A helped keep Ford afloat during the worst economic crisis in American history.

Buck Harness and His 1929 Model A

Buck Harness’s Model A fits perfectly into this chapter of Ford’s story. He valued the car both nostalgically and practically. “It was cheap,” he noted, remembering how nearly intact it was when he bought it. All he needed to do was repair the fenders.

His comments echo how generations of Americans have described the Model A. It was reliable, affordable, and built for everyday life.

The Model A carried Ford from the simplicity of the T into the streamlined modernity of the 1930s. For collectors like Buck, its endurance is part of its charm. His understated pride captures the essence of the Model A: a car that didn’t need embellishment to make history.

A Car That Endures

Today, the Model A is remembered not only as a technical achievement but as a cultural touchstone. It was the car of farmers, shopkeepers, and small‑town families—a machine that endured Depression‑era hardships and still sits in garages, waiting for someone like Buck to tell its story.

With the Model A, Buck’s collection arrives at the threshold of a new automotive age—one shaped by changing tastes, new technologies, and the steady march toward modern design.

Preserving Automobile History

What unites the founders of the companies behind Buck’s cars—men like William Dayton, Charles Rauch, Henry Ford, Harry Stutz, and the Stanley twins—is not simply their mechanical skill, but their willingness to risk everything on an idea.

They were visionaries who believed they could build something new, often with little more than a sketchpad, a workshop, and determination. Some succeeded spectacularly, others vanished quickly, but all shared the restless curiosity that drives innovators in every age.

The stories of these automotive pioneers mirror those of modern founders in various industries, such as Compaq, once considered the most innovative PC maker in the world; Blockbuster, which revolutionized how people watched movies at home; Borders Books, once known for creating large bookstores; and Polaroid, which transformed photography with near-instant film technology. The list of innovative founders and companies that once dominated their fields is long, but many have faded as the public chose different winners. Ultimately, inventors create, investors support them, but it is the public that determines who endures.

Buck Harness’s barn is more than just a collection of cars; it’s a time capsule. His collection captures the birth and early growth of an industry that transformed America over a century ago. Each vehicle tells a story of invention, ambition, and survival. Together, they trace the rise of an industry from its chaotic beginnings to its eventual consolidation. His cars remind us that history is not just abstract; it’s tangible and waiting to be uncovered by those eager to learn lessons from the past.

Collectors and restorers such as Buck derive satisfaction from the very act of restoration. Piece by piece, they bring machines back to life. In doing so, they become almost unwitting historians. Their work not only saves the cars but also preserves the stories of the people who dreamed of them, built them, drove them, and believed in them. The public benefits from this quiet dedication because, without it, much of this history would be lost.

So, this story ends as it began. One Man. Nine Cars. Restoring Automobile History. A legacy of automotive invention preserved by one man’s patience, skill, and love of restoration. Thank you, Buck Harness, for sharing your story with us.

December 17, 2025. Mark Rimel wrote this story based on several references, including 24/7 Wallstreet, American Heritage, American Business History Center, Audrian Automotive Museum, Autocar Always Up, Automotive American, Automotive History Preservation Society, Bonhams Cars, Certified Automotive Specialists, Classic Car Weekly, Classic Speedster, Conceptcarz, Diesel World, Early Electrics, Encyclopedia of Indianapolis, Etymology Online, Grandpa’s Old Cars, GrokiPedia, Hemmings Motor Club, Historic Indianapolis, Historic Structures, Historic Vehicles, History of Technology, House of Names, Horseless Carriage Club of America, Horseless Carriage Club of Missouri, Hyman Ltd., LM Classics, Motor Car, Motor Cities National Heritage, National Museum of American History, New England Historical Society, Sotheby’s, Simeone Foundation Automotive Foundation, Statista, The American Business History Center, The Free Social Encyclopedia, The Truth About Cars, Time Magazine, and Wikipedia.

Copyright & Use Restrictions

© 2025 Mark Rimel, Henry County Historical Society, and Henry County Museum. All rights reserved. No portion of this post may be copied, altered, printed, distributed, or posted online in any form without prior written consent.