The Lawrence Brown Story. A Missouri Original

Lawrence W. Brown

Dreamer, Inventor, and Entrepreneur. A Missouri Original.

Foreword

This account tells the story of the extraordinary life of Lawrence Brown, whose creativity and tenacity left a lasting impression on Henry County, Missouri. Brown was raised on a farm in the 1880s and lived a life shaped by early hardships. Even at an early age, he was a dreamer. He experimented, tested, and created until his ideas became reality. This is not a story of fame and fortune. Instead, it is a story of American ingenuity, perseverance, and the type of quiet courage that often goes unnoticed.

Section 01: Beginnings on the Farm

Lawrence Wesley Brown was born on Friday, February 25, 1881, in post–Civil War Missouri, on a farm nestled between Alberta and Coal, two small settlements about eight miles east of Clinton. He was the sixth of ten children born to Harry Plympton Brown and Samantha Azmarine Clark Brown. The Brown children arrived one after another for over 20 years: Hiram and Clyde, both lost in infancy; then Mary Violet (1874), Harry Paul (1876), Myrtle Bell (1878), Lawrence Wesley (1881), Eva Blanche, who went by Blanche (1884); then Nellie Clark (1886), Tracy Frances (1889), and their last child, Hallet Frank (1894).

Harry and Samantha were mid-nineteenth-century pioneer farmers whose lives were shaped by the daily grind of land and livestock. With 150 acres, average size for the time, the farm placed them firmly within Henry County’s middle class—neither rich nor poor, sustained by weather, willpower, and endurance. Every meal, every garment, every bit of comfort came from their labor on the farm.

From an early age, Lawrence exhibited an introspective nature. So much so that neighbors often observed him in the fields and thought to themselves, "wheels in his head," when they saw the boy resting on a hoe or rake handle, gazing toward the horizon like he was listening to distant ideas only he could hear. In an era that celebrated visible, physical labor, Lawrence's quiet daydreaming might have seemed like a sign of laziness. His future life would prove otherwise.

Neighbors remembered him as a "quiet, thoughtful, studious chap" who was often found puttering around in his father's workshop. Other kids hurried through their chores to go play. Lawrence was eager to play, too, but in a different way. He spent hours carving, sawing, and hammering pieces of wood until his vivid imagination was satisfied with his creation. Creating and figuring out how things worked was his form of play.

Section 02: Sudden Burdens

In 1894, Lawrence was just thirteen when his mother died—only six weeks after giving birth to Hallet. Three years later, in a cruel twist of fate, his father suffered a debilitating stroke. Lawrence’s older brother, Harry Paul Brown, had already married and moved to nearby Peelor, Missouri. That left the full weight of the farm—and the responsibility of providing for his siblings—to sixteen-year-old Lawrence. His oldest sister stepped in to help raise the younger children, but the bulk of the physical labor was his alone.

Without complaint, he dropped out of Star school, the one-room school he attended, and took on the role of family provider. He plowed fields, hoed crops, milked cows, and fed livestock, working from sunrise to well past sunset. It was a heavy responsibility, but Lawrence managed it without complaint.

Today, the idea of a sixteen-year-old managing an entire farm may seem unimaginable. But in that era, character was often shaped suddenly and by necessity. Hard times strengthened Lawrence's resolve and sharpened his thinking. They laid the foundation for a lifetime of practical problem-solving and invention.

Section 03: Kindled Aspirations

By the time Lawrence reached adulthood, hardship had shaped him, but it hadn’t hardened him. The daily chores of farm work filled his days, but underneath, a quiet flame flickered deep inside him, a burning desire to learn how things worked.

He absorbed mechanical logic the way some people absorb music: intuitively and with joy. Whether fixing a busted hinge or studying the workings of a hay press, he seemed to grasp not only how something functioned, but how it could function better.

Lawrence had a “self-starter’s mind.” Friends and neighbors remembered a boy who took the initiative to learn without waiting to be taught. He observed, tinkered, and tested his ideas to see what worked. Sometimes he succeeded. Sometimes he failed. Regardless of the outcome, he was optimistic, never discouraged. Tools weren’t just tools. They were invitations to explore and create. Processes weren’t abstract chores. They were puzzles to be solved. For him, the possibilities were endless.

Ideas came to him constantly. Some were likely influenced by the pages of newspapers, agricultural almanacs, or borrowed magazines filled with clever contraptions and bold new thinking of his time. But it wasn’t just what he read. Something deeper inspired him. Curiosity, yes, but also a kind of inner drive that didn’t depend on his circumstances. Lawrence wasn’t just trying to get by. He was trying to get somewhere.

Despite the heavy responsibilities of running the family farm, Lawrence's intellectual curiosity remained strong. He showed remarkable discipline, denying himself even the simplest of luxuries and leisure, choosing instead to save every penny. Each dollar brought him closer to the life he dreamed of. Using these savings, he enrolled in a short correspondence course in electrical engineering. He often studied by the hazy, soft glow of a kerosene lamp late into the night after the rest of the household had gone to bed.

Sidebar: Correspondence Schools of the 1890s

The image of Lawrence dedicating his spare time to studying is telling. Today’s youth study beneath cool LED light. Lawrence pored over lessons by the warm flicker of kerosene lamps, his ambition glowing stronger than the lamp. He absorbed the logic of circuits with the same quiet focus he once gave to shaping objects in his father’s workshop. For him, education, whether formal or self-directed, was a guiding light to a meaningful and purposeful life..

Sidebar: How Rural Homes Lit the Night in the 19th Century

Over time, that temperament became one of his greatest strengths. Lawrence aimed to make things that worked—and worked well. In that pursuit, he was unshakably patient, often willing to refine an idea for months or years before sharing it. What emerged wasn't a sudden flash of genius, but the steady burn of kindled aspirations.

That short electrical engineering course proved transformative, further fueling his desire for more comprehensive learning. Hallet, his younger brother, was nearly finished with school and prepared to take over the management of the now-thriving farm. The younger siblings were also making steady progress. In the fall of 1899, confident that the land and family were in capable hands, Lawrence made a bold decision to leave the only life he’d known to enroll at Warrensburg State Normal No. 2, known today as the University of Central Missouri. There, he immersed himself in the study of farm production, conservation, and economics.

Sidebar: The Transformational History of the University of Central Missouri

It was a remarkable shift—from the roughness of hoe handles and the scent of livestock to the quiet hum of classrooms and abstract ideas. Lawrence Brown's talent for managing both worlds hinted at a man whose roots ran deep in the soil but whose vision reached far beyond the farm.

Section 04: Inventive Return

When Lawrence came back from studying at Normal school in Warrensburg in spring 1900, about seven months after enrolling, he saw that his brother had "effectively managed the farm." Freed from the day-to-day tasks of plowing fields and caring for animals, he dedicated himself to lightening the load of rural life, tackling the burdensome chores that wore down his family members. His early inventions included a gas-powered homemade washer, a mechanized churning machine, a feed grinder, and a button-operated gate opener.

Sidebar: Powered Inventions Without Electricity

Each device demonstrated a practical way of thinking. Lawrence didn't build things for fame or fortune; he built them to serve a purpose. He found opportunity in mechanical gears and levers, whereas others might have taken hard work as fate. The washer made laundry easier for his sisters, the feed grinder made it easier to prepare feed for livestock, and the button-controlled gate added a touch of modern convenience to the farm, all built for the life he and his siblings lived.

While these devices relieved the burdens of life on the family farm, the distant rumble of the Industrial Revolution began to awaken the community's awareness that their world was evolving. Lawrence was listening. Through newspaper clippings, catalog advertisements, and word of mouth, stories of innovation inspired his creativity. He was prepared for the changing times.

Section 05 Harrows, Horses, and Poe

Throughout most of his twenties, Lawrence remained deeply involved in the day-to-day work of running the family farm. He “harrowed sod for corn,” a labor-intensive process that involved dragging a heavy rake-like implement over freshly broken ground to prepare it for planting. He bought and sold horses. One time, he noted taking a “few” of them to town and that “all kinds of fellows” were “talking about buying them at $200,” a respectable sum at the time, about $7,500 today. On another occasion, he wrote that he had “altered 3 colts,” a term referring to the castration of young male horses, a routine task, but apparently a little risky. One colt “very nearly caved John Halford’s ribs in,” a reminder that farm work can at times be unpredictable, even dangerous.

His daily chores were varied: hauling dried fruit to Martins, a local grocer; chopping wood; repairing “the big door at north end of barn”; fixing a broken plow handle; and taking on whatever odd jobs needed doing. It was a life of steady, unending tasks.

For Lawrence, though, it wasn't all work and no play. His intellectual appetite was evident in several ways. For instance, he considered subscribing to the Literary Digest, a widely read weekly magazine published by Funk & Wagnalls. The Digest offered condensed articles from American, Canadian, and European publications. Issues covered everything from current events and cultural stories to science and religion. He also noted a “special offer” to purchase the collected works of Edgar Allan Poe. This was most likely the 1905 New Century Library edition, a three-volume leather-bound set published by Thomas Nelson & Sons. Whether he bought them or simply liked the idea of reading them, it’s clear that Lawrence’s desire to learn and explore new things was persistent and sincere.

By age 28, his desire to learn had only grown stronger, with the idea of further education weighing on him daily. Finally, he took action. He packed his bags and traveled to Columbia, Missouri, where he enrolled in a series of short courses at the University of Missouri during the winter of 1909-1910. These were non-credit classes, but the subjects—Veterinary Science, Soils and Tillage, Animal Breeding, Stock Judging, Agricultural Botany, Soil Fertility, and Shop Work—speak volumes about his thirst for knowledge. His goal, though, wasn’t to earn a diploma. No, instead, he was pursuing knowledge for its own sake. To sharpen his mind. To develop new skills. He wanted to acquire knowledge that would satisfy his curiosity about the world around him.

During his stay in Columbia, Lawrence rented a room at 609 Turner Street, then a private residence. It was common for homeowners to rent rooms to students, and Lawrence shared his with Nash Howard, a young man from New Madrid, located in Missouri’s extreme southeastern corner, near the Tennessee border. Nash was “awful nice,” Lawrence wrote, though he admitted he would have preferred a room to himself “if it wasn’t so expensive.” Meals were also enjoyed at the house. After supper, Lawrence and the other boys would often play the fiddle and piano, taking a well-earned break from their studies to enjoy moments of camaraderie and light-hearted fun.

Section 06: And How About That Mary

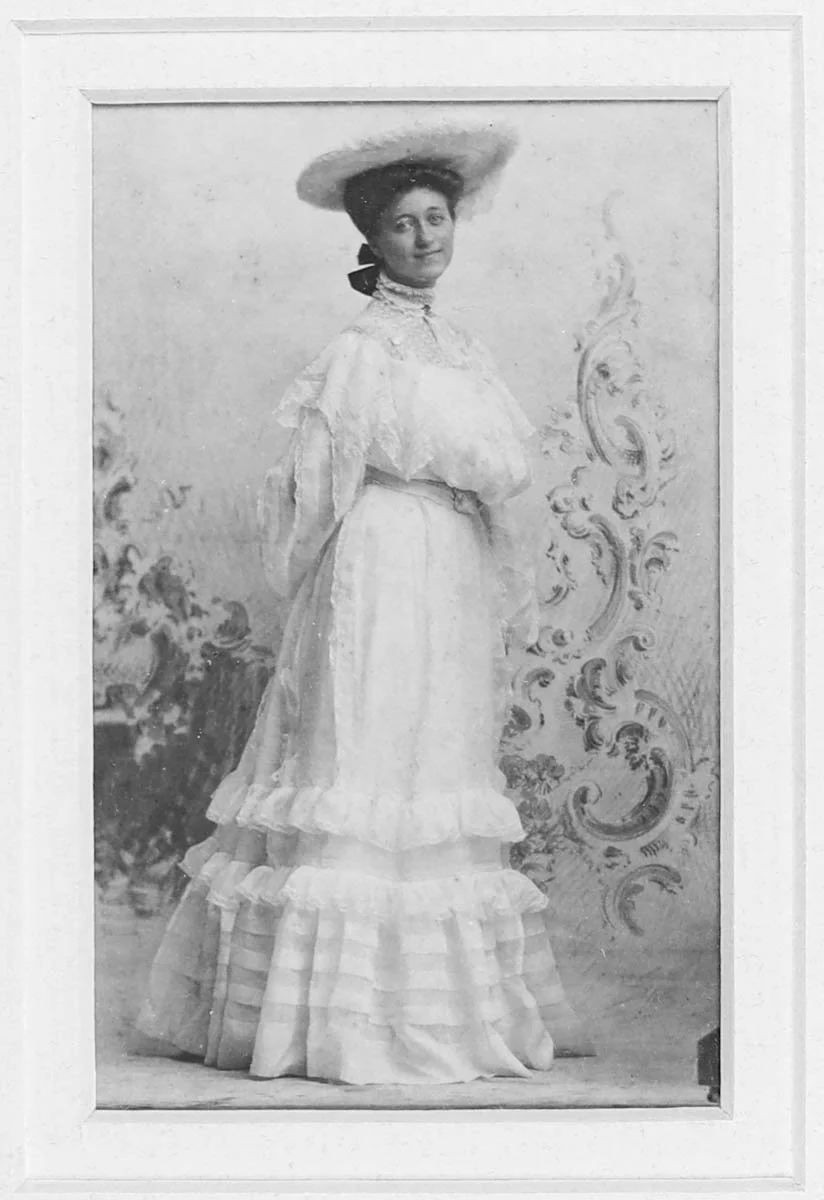

Mary Leona Doyle

She was cute as ever.

Lawrence thoroughly enjoyed his coursework, saying he liked studying “more each day,” but his mind wasn’t only on academics. Someone special had entered his life and heart: Mary Doyle, who lived on Clinton Street in Clinton. Although the details of their first meeting are unknown, Lawrence had been fond of her for years.

In May 1905, he recorded a vivid moment in his diary: “I saw Miss Mary out in the back yard in a sunny place stooped over, her hair loose and fallen down all around her face, sleeves rolled up to her elbows, towel in hand, giving her head a good old rubbing.” Days later, after spending time with friends on the square in downtown Clinton, he visited Mary at her home just a couple of blocks away. It was around 6:30 p.m. He scribbled in his diary that “She was cute as ever,” underlining the words to further express his feelings about her. On one occasion, Mary gave Lawrence a birthday gift—a copy of Ben-Hur—which he read and described as “just fine.”

While Lawrence was away at school, their love for each other grew, expressed through nearly daily letters. They missed each other deeply. Mary wrote that she felt lonesome but was “holding up pretty well.” That is, until the ache of separation overwhelmed her, and she had an “old-fashioned cry which lasted the greater part of the day and occasionally grew worse.” Her sister, Helen Doyle Peelor, whom Mary referred to simply as “Sister,” wrote to Lawrence to confirm Mary’s sorrow, saying she cried “almost enough salt water here the day you left for us all to have a bath.”

Lawrence felt the same way. He began his letters with affectionate greetings like “My Dear little Sweetheart” and “Dear old Girlie.” He often said how much he longed to be with her. In one letter, he said how much they had “advanced” in “expressing our sentiment for one another.” In another, he wrote, “I have just wanted to see you so bad all day that I don’t know what to do with my desire.” He continued, “I know you are just the best girl that ever lived and I realize it more all the time that no one could begin to fill the place you do in my life.” He also shared that he grew “tired of being around people,” but never with Mary. He could talk to her “with entire freedom and confidence.”

Their letters reveal a mutually tender and emotionally candid relationship. Lawrence’s words show a man unafraid to articulate his love for Mary with clarity and conviction. Mary’s words reveal a sense of vulnerability sprinkled with humor, namely an “old-fashioned cry” that “occasionally got worse,“ which would suggest a bond built on trust, warmth, and shared longing. For Lawrence, Mary was the person who made him feel whole, most fully himself. She was, in other words, the “one.”

Section 07: Wedding at 106 East Clinton Street

John and Matilda Doyle relax in rocking chairs at their home on 106 E Clinton, circa 1900, with daughter Mary standing between them.

On a Wednesday evening in early October 1910, Lawrence Wesley Brown and Mary Leona Doyle were married in the parlor of her family’s home at 106 East Clinton Street in Clinton, Missouri. The parlor showcased graceful decorations of goldenrod, cut flowers, houseplants, and a bank of evergreens. While the scent of fresh flowers, plants, and pine filled the air in the parlor, warm aromas drifted in from the kitchen down the hall, hinting that something delicious was to follow the ceremony. Together, the mingling scents grounded the ceremony in something familiar—a home filled with warmth, celebration, and anticipation.

Mendelssohn's "Wedding March" opened the ceremony, followed by the gentle melody of "Flower Song," a musical pairing that highlighted the evening’s sentiment. The bride carried roses and wore French white lawn, a delicate cotton fabric with a net-like texture and floral embroidery, accented with delicate Valenciennes lace. Its floral motifs added softness and refinement to her gown, reflecting the style of the turn of the century. The groom looked his best, as well, wearing conventional black attire.

Mary Doyle

French white lawn wedding dress accented with delicate Valenciennes lace.

Reverend Stewart of the First Baptist Church officiated in front of an intimate gathering of close friends and family, including Mary’s father, John Doyle, and mother, Matilda Doyle. After the vows and a round of heartfelt congratulations, the couple welcomed their guests for a two-course supper, served in the dining room. Following dinner came the traditional cutting of the wedding cake, which was lovingly homemade by the bride's mother. The couple received many gifts, including fine china, cut glass, and silverware, which were cherished not only for their quality but also for the lasting relationships and well-wishes they symbolized.

After the wedding, Lawrence and Mary stayed a few days in Sedalia and attended the Missouri State Fair. When they returned, the couple spent three years on the Brown family farm before moving back to Clinton to live in the same house where they had exchanged vows. Mary’s childhood home became their own. It held her memories, but soon it would be filled with new ones they would create together.

The reason for moving to Clinton and Mary’s family home is not known. What is clear is that it was a full household. Besides Lawrence and Mary, her mother and father, and her grandmother also lived there.

Section 08: A Town of Iron and Ingenuity

Lawrence’s return to Clinton marked the start of a new chapter—personally and professionally. For someone whose early youth had revolved around shaping wood and tinkering with gears and levers, Clinton opened a new world of opportunity and direction.

He found steady employment at Industrial Iron Works, a fixture in the local economy since the early 1880s. A. H. Crandall founded the company, but it was later acquired by machinist William F. Hall in 1894. The shop expanded over the decades from a simple repair business into a regional machine shop that designed custom-built machinery, castings, and other tooled parts. They were most notably known for gasoline-powered “Missouri” engines that were widely used in workshops, factories, and farms. People around town long remembered watching molten iron poured into molds in the back room of the main building, a kind of public theater of industry. For Lawrence, the company offered more than work; it reflected the kind of thinking and precision he’d valued since childhood.

Lawrence moved across departments, picking up the practical knowledge of fabrication and mechanical systems. That range of experience, combined with the quiet focus he’d always brought to his work, made him a welcome presence in the shop. Though he rarely called attention to himself, his knack for problem-solving stood out.

Still, the steady rhythm of an industrial shop didn’t last. He became increasingly restless. After three years, Lawrence left Clinton to explore the oil fields in Oklahoma and Texas—a booming economy that drew men with nothing more than a dream. It was reminiscent of the gold rushes in the 1800s.

What motivated Lawrence to leave home for the oil fields, or what he did when he got there, is unknown. Mary's thoughts on his decision to leave home are also unknown. Traveling to and between Oklahoma and Texas must have been arduous in those days. There is no record of where he stayed or his living conditions. Working in the oil fields was not an easy task. No doubt the work was hard and the hours long. How much he was paid, how he was paid, or whether he was paid, no one knows. Whether it was an attempt to build wealth or simply to learn something new, it is a chapter in his life that will remain a mystery.

As with his stint at Industrial Iron Works, he didn’t stay long, maybe a year, no more than two. The draw of Clinton and his family drew him back, this time with a clearer idea of what he wanted from life. In a back room of his house, he began putting his ideas on paper. One of his earliest designs was a spring wheel, meant to replace standard pneumatic automobile tires. It didn’t work as planned, but the project marked a change in his thinking. Lawrence wasn’t just tinkering anymore—he was creating with purpose.

Sidebar: No Flats, Lawrence’s Spring Wheel Concept

Looking at his path—from farm work to formal study, from shop floor to oil field, and finally to independent inventor—it’s clear he was after more than a job. His spring wheel idea may have failed in practice, but it reflected his instinct: solve real problems, test bold ideas, and never stop learning. In that way, Lawrence wasn’t chasing innovation. He was living it.

This pursuit, even in the face of setbacks, speaks volumes about his drive to create something lasting. His journey reminds us that meaningful innovation often emerges not from a single breakthrough but from continual exploration, adaptation, and quiet resolve.

Section 09 The Changing World of Lawrence Brown

Understanding what stirred Lawrence Brown’s imagination means stepping into the extraordinary momentum of the era that shaped him. The 1880s world of hooves and lanterns, where evenings glowed dimly with kerosene and journeys were measured in long miles by foot, horseback, or horse-drawn buggies, was steadily shifting beneath his feet.

By the time Lawrence turned sixteen and took responsibility for the family farm, the ground trembled with change: iron tracks spread across the prairie and town, crisscrossing Henry County and Clinton specifically. The Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad (MKT) laid its tracks in the 1870s, followed by the Kansas City, Clinton & Springfield Railway (KCC&S) in 1886. By 1901, the town had become part of the St. Louis–San Francisco Railway network, connecting Clinton to places that once seemed impossibly far away. The railroad didn't just move people or freight; it redefined the very concept of time. The roar of steam engines replaced the quiet rhythm of wagon wheels, and Clinton began transforming from a small rural town into a vital commercial junction.

Even before voices traveled by wire, telegraph lines had already stitched Clinton into the national conversation. Installed by the 1870s, they let messages travel hundreds of miles in minutes. By the late 1890s, telephone wires began appearing. By the early 1900s, Clinton had switchboard operators manually patching calls across homes, businesses, and regions—connecting voices not just across town, but across states. For the first time, distant voices could be summoned in real time, expanding the boundaries of community and commerce.

With steel rails came brick storefronts and the hum of commerce. Between 1890 and 1920, Clinton experienced a peak in commercial construction, and its square blossomed into a hub of banks, hotels, grocers, hardware stores, distributors, and manufacturers. The optimism of the age was etched into the two-story facades that still stand today. This momentum rippled outward into residential neighborhoods, as well. By the time Lawrence was 30, Clinton’s population had more than doubled from about 2,000 to over 4,600 citizens. Dozens of homes—Craftsman, Victorian, Italianate, and other styles—were built for railroad workers, business owners, and families staking their futures on a town in full bloom.

Lawrence would long have been aware that Thomas Edison invented the light bulb in 1880. By the early 1900s, electric streetlamps began to pierce through Clinton’s dark nights, courtesy of the Green Power & Light Company and later the West Missouri Power Company. During the 1920s, homes and storefronts glowed with filament light. Rooms once lit by the dim pulse of kerosene now radiated with steady incandescence. Daily routines were reimagined. People could work longer. Dinner could be held later in the day. Casual time was extended, allowing families to read or play games well into the evening. Gathering with family and friends at night became commonplace. Porch lights both welcomed guests and served as beacons of safety.

For Lawrence, the inventions of his era redefined what was possible. It marked the beginning of a pattern he would witness again and again—electric power and light bulbs, telephones, radio, trains, automobiles and airplanes, photography and motion pictures, phonographs, and typewriters—familiar ways overturned by invention that reached farther, faster, and deeper than previous generations could imagine.

Section 10: International Auto Buggy or Auto Wagon

Lawrence Brown's fascination with everything mechanical naturally included the emerging world of automobiles. According to The Clinton Eye, in 1908, he became one of Clinton's earliest car owners when he purchased a second-hand vehicle from W. B. Kyle, a local grocer and real estate agent. The car was a 1907 International Auto Buggy. It had hard rubber tires and a two-cylinder air-cooled engine with chain drive. It boasted "about 20 miles to the gallon" of gasoline, which cost about ten cents per gallon at the time. It also required a special grade of oil. The car could carry "about six passengers” and featured a removable back seat, making it versatile for its day. Surprisingly, according to Brown, it had a decent ride.

International Harvester

1907 Auto Buggy. Lawrence Brown’s first car.

Having lived on a farm, Lawrence thought of this machine as a versatile vehicle. It was more useful to him than just a recreational or touring car. He adapted it for work, hauling produce from the farm to Clinton. Its wood-spoked wheels allowed it to handle the roughest rural roads. The wide wheel spacing matched up perfectly with wagon wheel ruts, and the large wheel size prevented it from slipping into small holes. In rainy weather, Lawrence would wrap chains around the rear wheels to drive through "mud up to the axle," a test he often put it through.

Lawrence’s first car held a special place in his heart, recalling driving it as the "greatest thrill I ever got out of a car." As of September 1937, Lawrence still owned this first automobile, keeping it tucked away in a small outbuilding at his home. Remarkably, it remained operational under its own power even decades later.

This cherished vehicle remained part of Lawrence's and Clinton's story for many years. At the Henry County Fair on August 12, 1954, he proudly drove his "ancient 1907 International two-seated car" in the Old Cars parade. Shielded by a white umbrella against the August sun, the car carried four of his grandchildren—Larry and Eddie Brown, Chris and David Walker—clinging to its sides. This later appearance not only confirmed the car's survival and operability but also celebrated its enduring place in both family memory and community tradition.

Lawrence’s Auto Buggy had a colorful history before he acquired it. According to local accounts, it had once been "wrecked by someone driving down a hill on the way to Deepwater, Missouri" when its brakes failed. The driver "threw it in reverse and wrecked the motor." The damaged underside remains visible in the Henry County Museum’s preserved display of the car.

In terms of automotive classification, the surviving vehicle bears a closer resemblance to the 1908 International Auto Wagon, an early pickup-style model. Adding to the mystery, The Henry County Democrat, reporting on the same date as The Clinton Eye, referred to Lawrence's vehicle as an "old truck"—not a car—and listed T. L. Jones of Urich as the original owner, not W. B. Kyle of Clinton. These competing sources raise a compelling question for automotive historians: Is the vehicle preserved in the museum the 1907 Auto Buggy or the 1908 Auto Wagon?

Section 08, Sidebar: The Allure of the Automobile

Section 11: The Missouri Bird Takes Flight

Lawrence Brown had a mechanical mind combined with a child's sense of wonder. It's no surprise, then, that he developed an early fascination with flight. In 1921, when Lawrence turned 40, his strong interest in anything airborne led him to invent a small toy aeroplane, soon referred to as an airplane, as the term gained popularity.

Sidebar: You Say Aeroplane and I Say Airplane

His first design utilized a lightweight cardboard tube, similar to a soda straw, for the fuselage, real feathers for the wings, and a rubber band attached to a makeshift propeller. Once the propeller was wound up and the little plane released, it would sail through the air for several feet. Neighborhood children loved it. Within weeks, parents were asking Brown to make his toy planes for their kids. A local baker even commissioned him to produce them as promotional gifts for his bread, an early sign that Brown's creation had both play value and marketing appeal.

Encouraged by the demand, Brown improved the plane's design. By 1923, he was prepared to start production. It wasn’t a slow, test-the-waters approach to manufacturing. Instead, it was a bold, full-scale leap into a new world.

In an era when Clinton phone numbers had only two or three digits, and international calling was nearly unheard of, Lawrence Brown built a supply chain that stretched across the United States to South America. He sourced specially treated paper tubes for the fuselage from The Stone Straw Company in Washington, D.C. They were delivered in lots of 60,000 units. From Akron, Ohio's Goodrich Company, he purchased rubber bands in lots of 50,000 units. The drive shafts were crafted from South American balsa wood, praised by Scientific American for its exceptional combination of lightness and strength, and shipped in quantities sufficient to produce 250,000 shafts.

It wasn't just the logistics that were amazing; it was his ability to calculate material quantities, negotiate acquisitions, design the tooling, and train a small team to keep production moving at an ever-increasing pace. And he did it without consultants, venture capital, or a national distributor. He did it out of curiosity, driven by a vision, and sheer determination.

In June of 1923, Brown officially opened the Missouri Bird Manufacturing Company in four rooms above the Docherty Fuel Company office, a coal and wood supplier in Clinton. Initially, the little plant offered two models: one with paper propellers, the other with celluloid, an early form of plastic, each available in vivid colors. They were bright, sturdy, and built to fly.

Lawrence hired a small but efficient team of five men: Doyle and James Peeler, Oliver Kensinger, Robert Douthat, and Richard Carmody. Together, they assembled an impressive 1,500 planes per day using machinery Brown invented himself, including tools for bending wires, cutting and mounting propellers, and precision-cutting lightweight materials.

The team followed a precise, step-by-step method for production, refining each stage for speed and consistency. Their process was honed to precision: folding propellers, fitting drive shafts, anchoring rubber bands with a bent wire, inserting cup-shaped tin washers to reduce resistance, and affixing propellers, tail fins, and rudders for controlled flight.

The Missouri Bird was built to fly. And it did. What began as a hand-cut toy evolved into a dependable, factory-built product, carefully assembled in a second-floor workshop above a coal office. Brown was launching his idea straight into the heart of Main Street America. His planes found their way into the hands of children, families, and advertisers across the region. The little flyer was proof that imagination, properly guided, could become reality.

Section 12: Missouri Bird Factory Sold to Investor

In March 1925, with daily production surpassing 3,000 toy planes, Lawrence Brown is said to have sold his stake in the Missouri Bird Factory to a Dallas-based investment firm for $30,000, or the equivalent of roughly $525,000 in 2025 dollars. The sale included his designs, patents, and custom-built manufacturing equipment, and Brown was to stay on for at least a year to oversee operations.

Local newspapers, the Henry County Democrat and The Clinton Eye, announced the deal. After that, nothing: no follow-up announcements, no visible branding changes, no leadership changes. Like his venture into the oil fields years before, the reason the sale was never finalized remains unknown. What remains certain is that Brown continued the business and production as if a sale had never occurred.

Section 13: Lawrence Brown Expands Reach

The planes, first released for the Fourth of July in 1923, had by 1925 sparked national enthusiasm. Orders flooded in—some buyers requested as many as 1,000 planes, with one record-setting order: 25,000 units from Peters Shoe Company in St. Louis. Brown's little four-room factory made over 100,000 toy planes in 1927. It was a testament to the product’s widespread appeal and Brown’s ability to ramp up production.

To further increase demand, Lawrence hired three traveling sales agents to promote the toy planes across the country. Among the agents, one stood out: Ed Munsel, who operated out of Iowa and reportedly sold half of the company's production. Munsel had previously co-owned the Busy Bee Confectionery with George Gregg, located on the southwest corner of Clinton's downtown square, which Diamond Drug later occupied. His involvement adds a touch of hometown pride to the Missouri Bird story. It’s proof that its flight path began in Clinton.

Somehow, without formal education, Lawrence Brown managed to engineer and implement an entire production ecosystem. He sourced materials from abroad and designed his own machinery. Then he streamlined operations to meet growing demand. What began as a single handmade toy evolved into a well-coordinated production line. The toy was built from scratch, built to last, and unmistakably Brown’s ingenuity at work.

Section 14: More Territory, More Growth, More Planes

Lawrence Brown and his eldest son, Herbert, drove to Oklahoma City and Tulsa in December 1928. They likely aimed to establish new commercial ties or expand their distribution network. Their travel expanded the following year. In February 1929, they spent a month in New York City attending the Toy Fair, one of the largest events in the toy industry.

In a letter home, Lawrence described the eastern countryside as "very pretty" but "quite cold," providing a glimpse of the wonder and discomfort that came with winter travel across states in a 1920s-era automobile.

In March, Lawrence unveiled a new toy airplane, initially named the "Spirit of America," but it was soon renamed the "Spirit of Flight." Renaming the little plane might reflect the aviation enthusiasm sparked by Charles Lindbergh's Spirit of St. Louis, which gained worldwide attention after his historic transatlantic flight in 1927. Unlike the Missouri Bird, this model had adjustable wings, letting it fly straight or in a loop, mimicking the movement of a boomerang, which became its nickname—boomerang plane. Lawrence believed this model would sell better than the Missouri Bird.

Three-story “barn factory” built behind Lawrence Brown’s residence.

Building on Lawrence's ability to combine his creative engineering skills with marketable designs, the two toys became the core of his advertising novelty business. To scale production of both models, he began constructing a three-story barn factory behind his home at 106 East Clinton Street in March 1929.

That summer, a significant milestone marked the company's growing reach. In June, Lawrence's factory fulfilled an order of 2,000 toy gliders for a merchandising company in Sydney, Australia. For the American market, Lawrence stamped the wings with Spirit of Flight. But for the Australian shipment, he made a thoughtful change—engraving the wings with The Southern Cross, referencing the well-known constellation visible only in the southern hemisphere, and nodding to the celebrated aircraft that completed the first trans-Pacific flight just a year earlier. This wasn't just clever branding; it was cultural awareness and marketing instinct at its best.

In that same month, the Henry County Democrat and The Clinton Eye reported that Lawrence had received a certificate of incorporation from the Missouri Secretary of State for the Missouri Bird Manufacturing Company. However, nearly all later references to his firm used the name Brown Manufacturing Company, indicating the initial reports were either premature or incorrect.

Regardless of the paperwork, Brown's operation was gaining momentum. He acquired a Willard #3A punch press, hauled from Leeton to Clinton by Mason Brothers truck. This single-action machine was ideal for tasks like cutting and shaping lightweight materials. With it, Lawrence expected daily output to climb from 3,000 to as many as 6,000 toys—a leap toward true industrial production.

Section 15: Trial by Ice and Fire

Tragedy struck when a fire broke out during an excessively bitter-cold spell at the Browns’ frame house on Saturday, January 18, 1930. The family discovered the fire shortly after breakfast. Because of excessive stoking of logs in the fireplace, the chimney flue overheated, leading to a fire between the living room ceiling and the floor above.

Extreme weather conditions made firefighting nearly impossible. With the outside temperature a brutal 22 degrees below zero, a record low, the Clinton Fire Department immediately faced setbacks. Firefighters discovered that a hose connected to a fire plug at the corner of Clinton and Main Streets had frozen solid. A second line laid to the hydrant at Ohio and Second Streets suffered the same fate. Firefighters used gas blow torches to thaw the blocked hydrants.

When a crew finally brought the pumper into service at Clinton and Main, the nozzle quickly froze, causing the hose to burst in several places from the sudden pressure. Despite being "covered in ice," the brave firemen persevered, managing to replace broken sections of hose while simultaneously working to thaw the frozen nozzle. Firefighters worked through the night. With the house now cloaked in sheets of ice, the fire was finally extinguished, but the damage was severe. The “entire second floor was burned, and the first floor was damaged nearly beyond repair.” The house, initially built decades ago by John Doyle’s brother, Dan, could no longer be occupied.

Mary’s father, John Doyle, aged 85, was rescued unharmed from the second floor. Thankfully, John, Lawrence, Mary, and the children were able to escape to safety. Neighbors stepped in and helped save nearly all household belongings, especially on the first floor.

In the immediate aftermath of the fire, the Brown family leaned on those around them. For a time, they stayed with different family members separately. Some lived with the family of Ray and Tracy Mills, Lawrence’s brother-in-law and sister. Others, including John Doyle, lived with Doctor Edwin and Helen Peelor, Mary Brown’s brother-in-law and sister. This much-needed help, although unspoken, was a reminder that family was close by when things seemed to be falling apart. An apartment was also quickly built for the family on the third floor of the Bird Factory, which was situated directly behind the now-charred remains of their former home. It offered temporary refuge while plans for rebuilding took shape.

106 E Clinton Street

The Brown residence, rebuilt after the devastating fire, stands restored once more.

With careful planning and clear objectives, reconstruction began almost immediately. Contractor Charles Albin oversaw the renovation, which started with the excavation of a full basement. A large sun porch was built, with windows facing east, south, and west. This allowed plenty of natural light into the kitchen and dining area. The living room was enlarged to a spacious 15 by 30 feet. Wide porches were added. The restoration designs aimed at giving the house a sense of grace and warmth.

What had been destroyed by fire rose again—not just as a house, but as a home filled with resilience and community spirit. The same resilience and determination that powered Lawrence's business now guided the rebuilding of his family's life.

Section 16: Reinvention in Hard Times

In the weeks after the rebuilding of his home, Lawrence Brown's business took off. A large post-holiday order arrived from Ennis-Hanly-Blackburn Coffee Company, a Kansas City-based business renowned for its Golden Wedding coffee and other specialty products. They requested "without limit" all the promotional toy planes Brown could produce, but with a catch. They asked for a custom-sized, slightly smaller version of the Spirit of Flight model. The special request order demonstrated the lasting appeal of his products, even as the country entered the early months of the Great Depression.

Brown adapted quickly to shifting economic conditions. By 1932, he was designing new advertising novelties and toys with his now familiar flair. One release featured adhesive windshield stickers for automobiles, intended for business promotions. Another was a launchable toy disc called "Shoot the Moon," powered by elastic and engineered to soar 250 feet before fluttering back to Earth like a butterfly. The first order came from Scott Grocery and Market on East Green Street, where Green Streets Market is located today. The grocer quickly earned a reputation as "a very popular man with small boys as long as his supply held out."

Even when the economy got tough, Lawrence stuck to what he knew: building useful, often playful things, chasing ideas, and trying to make something people would enjoy. He supplied firms with custom-made promotional pieces and made toys that caught the breeze just right—simple, clever, and joyful. That mix of mechanical skill and good business sense kept his factory going.

Section 17: Moving Forward in Changing Times

Signs of recovery were evident by early 1933, at least in Lawrence Brown's world. In February, he and his family traveled to Enid, Oklahoma. They visited Lawrence’s sister, Mrs. S. J. Shoults, and her family. However, the primary purpose of the trip was to meet with three sales representatives from the Southwest territory, including Mr. Shoults, who was the Dodge City, Kansas, agent for Brown Manufacturing. All three agents were “extremely optimistic regarding the trade of the coming season.” The meeting confirmed what Brown had hoped: that markets were waking up again.

Prospects with Continental Oil and Phillips Petroleum looked promising, as well. The mood among their representatives was as optimistic as his own agents. "The depression was on its last lap," Brown observed with guarded confidence, a rare comment from a man more inclined to invent products than analyze trends.

That spring, signals grew stronger. After returning from Tulsa, Lawrence reported that banks had plenty of cash reserves on hand and that "extreme optimism" was common in the region. His belief in an improving economy moved him to action. Brown created yet another toy: Brownie's Machine Gun, a paper-based device that imitated the cracking sound of a firecracker. Loud, fun, and creative. It showed his talent for turning simple materials into impressive products.

Lawrence W. Brown

Portrait of Lawrence by professional photographer Elssworth Marks.

Clinton's own "Bird Man" had built an export empire out of paper, plastic, wood, and clever ingenuity. Production was now booming. By March 1934, Brown's factory was turning out 20,000 toys a day—airplanes, boomerang flyers, noise-makers—each crafted with artful mechanical charm and shipped to every state in America, as well as to Canada, Mexico, Central and South America, the West Indies, Australia, England, and South Africa. The scope was global, but the designs were purely local.

Lawrence also pursued food manufacturing. One of his latest products was Brownies Breakfast Food, which was blended with wheat, oats, and barley. The cereal was meant to be cooked and eaten warm, making it especially suitable for colder seasons. Demand grew steadily, with large orders reaching well beyond Henry County. "Iowa people certainly like 'Brownies,'" Brown said, referring to a shipment of 500 cases headed for Ames. The cereal's success represented a new kind of invention: simple in ingredients, yet grand in its potential. It was a promising venture, just as circumstances would soon test his ability to keep it going.

Section 18: Fire, Ashes, and Adaptation

Disaster struck the Brown Manufacturing Company's barn factory in the early hours of November 5, 1936. Flames tore through the three-story wooden structure behind the Browns' home. Hearing the crackling of the fire, Herbert Brown discovered the blaze around 4:40 a.m., an estimated 15 minutes after it had begun. The east wing was already engulfed. He quickly raised the alarm and tried to rescue the family's 1933 Chevrolet sedan from inside the building, but it was too late. The heat was overwhelming, so he gave up when the engine refused to start. Ultimately, the flames consumed the car.

The blaze ignited and spread quickly, caused by the spontaneous combustion of grains stored in the building for the company’s popular breakfast food, Brownies. The fire was further fueled by balsa wood, celluloid, paper, cardboard, inks, dyes, and three tons of packaging material. All that was left of the wooden structure and its contents were "smoldering ruins." Years of documented designs and ingenuity were gone forever. The machinery was also rendered useless: a planer, a drill press, a hoist, eight printing presses, several saws, a perforator, and a lathe.

The loss to the business was total. No inventory. No equipment. No production. Twelve employees lost their jobs, including four traveling agents. The fire shook the neighborhood, as well. Nearby homes and buildings were scorched, and paint blistered.

Lawrence was away on business in Springfield and unreachable. But upon his return, he didn't retreat. Within weeks, he requested a permit to build a one-story fireproof structure on the same site. This time, the plans were not for a factory, but for a space dedicated to storage and experimentation. The city council approved the plan, noting that the new building would be "attractive" and would not disrupt the neighborhood's character.

Meanwhile, Lawrence leased space in the old Oberman Overall Factory on the northwest corner of Washington Street and Grand River. Of the eight printing presses thought to be lost in the fire, he salvaged three and purchased two more. The Oberman building, once part of Clinton's garment industry, now hosted the rebirth of Brown's mechanical creativity.

Sidebar: The Oberman Overall Factory

Section 19: A Shadow of Sadness

Just two months after a fire destroyed his toy factory, Lawrence Brown suffered a more personal tragedy. His wife, Mary Doyle Brown, contracted pneumonia and died, surrounded by her family, on Wednesday, January 27, 1937, at 11:45 a.m. She was 51 years old. Her daughter, Mrs. Helen Geraghty, had come home to help care for her during her final days.

Mary's death cast a long shadow over Clinton. Born in Brownington, Missouri, in 1885, she moved with her parents to Clinton at age four and considered it her home for the rest of her life. She and Lawrence raised five children together: Herbert Doyle (1912); Helen Clark (1914); Paul Edwin (1916); Matilda Churchill (1924); and Mary Jean (1928). At the time of Mary’s death, all except Helen (Mrs. Helen Clark Brown Geraghty) still lived at home.

Mary was known as a devout member of the First Baptist Church and the Order of the Eastern Star. She was a woman of warmth, grace, and quiet strength. Neighbors described her as kind and friendly, someone who rose to "the greatest heights" as a mother and a companion. To Lawrence, she was more than a partner; she was an advisor and a source of inspiration as he built his business from the ground up.

Her passing was felt not only in her home and church but throughout the wider community. As one local obituary stated, "The death of Mrs. Lawrence Brown casts a shadow of sadness over the whole community. The widespread grief well attests the great esteem for the deceased, as well as for the bereaved husband and children."

Section 20: Play and Production in Clinton

What started as a family improvisation became Lawrence Brown's biggest hit. One evening, with chess pieces missing, Brown got the idea of creating a game using marbles and a modified checkerboard. The result was Chinkerchek—a lively, strategic, and highly social game designed for two to six players. Each player used ten colored marbles to move across the board, aiming to reach an opponent's territory. Simple, visual, and unexpectedly competitive, Chinkerchek quickly gained popularity.

No advertising. No sales agents. Yet more than 2,000 units were sold in the Clinton area almost immediately. Soon after, there were widespread shipments to the West Coast and Southwest. Supplies became strained as demand continued to soar.

Each game board was crafted from quarter-inch, three-layer wood panels milled in Washington State. In Clinton, the boards were shellacked, drilled, stamped, printed, and edged with a custom mold. Several versions of the game were created. Not surprisingly, the most affordable version was the most popular.

Alongside the game, they continued making Brown's boomerang flyers and Brownies cereal. The factory was alive with activity, with production going around the clock. "It is a busy place," wrote The Clinton Eye. "The game is catching on like wildfire all over the nation."

Chinkerchek's momentum was unstoppable. In a way, it had become the community's heartbeat. It demonstrated how play, production, and pride could coexist. And how misplaced pieces of a chess set could change everything.

Oberman Overfall Factory building, circa 1939.

Standing left to right: Matilda Brown Walker, Helen Brown Geraghty Long, Myrtle Barrows, Herbert Brown, Leona Holcomb, Helen Rentschier Epple, and Fern Harris Taylor. Seated are Dan Geraghty and Lawrence Brown, who is holding a Chinkerchek board game.

The factory wasn't just a workplace; it was a gathering place, too. On February 25, 1938, employees surprised Lawrence with a celebratory supper on the first floor for his 57th birthday. They arranged tables in a U-shape around a towering, candlelit cake. After dinner that included sandwiches, pickles, salads, baked beans, and coffee, the workers transformed the factory floor into a playground. Young guests rode low-wheeled carts used for hauling Chinkerchek boards. Adults joined in. Some tried roller skating. Others played the very game they manufactured daily, but seldom had time to enjoy it. Laughter echoed through the room.

Section 21: Vision and Velocity

To some, Lawrence Brown was just Clinton's toy man, but he was more than that. He was a restless thinker, always pushing the boundaries of design and what was possible.

In April 1938, Brown spoke at a Chamber of Commerce luncheon on one of his favorite topics—aviation. "Man has not yet learned the ABCs of flying," he began, tracing the arc of human ambition from myth to machine. Despite decades of progress, Brown argued, genuine innovation in air travel remained out of reach. Modern planes still depend on fixed wings and propellers, essentially "skidding" through the sky, as he described it. That kind of motion, he believed, was inherently unstable. "It is impossible to stop a plane, turn it at right angles, or run it in reverse," he warned. "Until that is possible, air travel will be unsafe."

Brown wasn't suggesting copying bird-like wings exactly, as he doubted such propulsion could ever be engineered. However, his challenge was clear: if aviation was to evolve, it needed to mimic nature more closely, rather than rely on outdated mechanical tricks. To drive his point home, Brown referenced Thomas Edison, paraphrasing the famous inventor's view that human progress was far from complete. Edison once observed, 'We don't know a millionth of one percent about anything.' Brown echoed this sentiment in his own way, suggesting that just 1% of human ingenuity had truly been tapped. There was still much left to invent.

He also talked about Chinkerchek. The factory's best day produced 1,575 units, and the game was available in 47 of the nation's 48 states. "We expect orders from Maine any day," Brown joked, as he handed out two game sets: one to the first person who arrived at the luncheon, and one to the last.

Section 22: Innovation at Brown Manufacturing

Always looking to streamline production, Lawrence focused on reducing the number of employees needed to drill the 121 holes in each Chinkerchek board, from six down to one. Previously, each worker drilled a single hole at a time, making it the slowest part of the process. Fred Myer, a machinist at Industrial Iron Works and one of Lawrence’s former colleagues, devised a machine capable of simultaneously punching all 121 holes into the wooden panels. It dramatically improved both time and labor efficiency.

In August 1938, as the holidays approached, 47 of Brown’s workers assembled, boxed, and shipped 39,600 games to merchants across the country. That’s a huge number for something that had begun at a kitchen table.

The more games sold, the more marbles needed. Each game board required 60 marbles. The August shipments alone demanded 2,376,000 marbles! The glass factory in Ottawa, Illinois, Brown’s supplier, was sending shipments by the carload. As glass marbles became harder to find, Lawrence turned to wooden marbles for cheaper sets.

Section 23: Brown Manufacturing’s New Home

Built in the mid-1890s for Harness Business College, this striking three-story brick building, with its ornate central tower, became home to Brown Manufacturing in 1938.

Sidebar: The Many Occupants of the Harness Business College Building

To store the materials needed for making the Chinkerchek board games, Brown Manufacturing purchased the building known as the “Harness Business College” at 121 North Second Street on Tuesday, December 13, 1938. According to Lawrence, the three-story brick structure was well-constructed and in good condition.

In 1941, Lawrence moved his factory operations from the Oberman building to the recently acquired Second Street facility, initially built for the Harness Business College. Windows on all sides of the brick building provided welcome daylight year-round and cool breezes from spring through fall. An elevator served all three floors. Each floor was open, with only a few partitioned rooms. To Lawrence’s grandchildren, the wide wooden floor aisles were an invitation to roller skate. For factory production, the first two floors were filled with machinery: bench saws, reciprocating saws, band saws, drill presses, grinding wheels, printing presses, and an oversized paper-cutting machine. On the third floor was a shooting range where Lawrence, his sons Herbert and Paul, and invited guests would practice target shooting and take their minds off business.

Section 24: Clothespins and Creativity

By early 1939, Lawrence Brown had unveiled another surprising invention: Snap Builder, a modular toy system crafted from snap clothespins. Designed for "children from six to sixty," it featured beams, boxes, wheels, and pre-cut grooves that allowed the clothespins to connect securely with other pieces. Kids could build wagons, windmills, and over a hundred different models, each one sturdy enough to be picked up and carried around the house.

Wheels spun on six-penny nail axles, adding motion to the child's imagination. "Mother can buy clothespins to use on wash day," Brown joked, "and Johnny can use them the remainder of the week on his Snap Builder." Snap Builder was sold in two sizes: $0.50 for the small set and $1 for the large. Affordable, especially in an economy still finding its footing. Like Chinkerchek, it drew on Lawrence’s knack for reimagining everyday materials as something joyful.

Section 25: The Rotary Rocket Story

What began as a homemade Fourth of July display ended badly in 1939. While helping his daughter, Lawrence Brown burned both hands, with the left so badly that he had to stop the demonstration and call a doctor. The injury healed, but it marked a turning point—from celebration to serious experimentation.

Months later, Lawrence Brown's ambitions soared. In partnership with Midwest Display Fireworks of North Kansas City, Lawrence introduced a rotary rocket ship designed to both dazzle and glide. Developed in an isolated ravine on the Missouri River bluffs, the rocket featured spinning wings that orbited as ignited propellant burned at their tips. If all went well, the ship would launch a thousand feet skyward, erupting in sparks and color. After the propulsion burned out, the wings would shift into a locked glide, allowing the rocket ship to sail gently back to Earth. It was as reusable, impressive, and deeply unconventional as it was a mechanical marvel.

The real challenge? Developing a rocket fuel that burns at high pressure without detonating. After two years of testing, Midwest Display Fireworks announced they had succeeded. While they developed the propulsion system, the rotary rocket design was Lawrence Brown's. This chapter of his life demonstrates his ongoing passion for problem-solving. At age 58, he wasn't slowing down; he was picking up the pace.

Section 26: Toys in Orbit

Lawrence Brown’s rotary rocket ship, renamed Rotary Spaceship, succeeded in both imagination and engineering. Only one problem—no fireworks company would accept his designs. So, Brown built the rockets himself. Built to last, he created tubes he claimed were fireproof and patent-worthy. Lawrence had sketched out a twin-wing version, but rising manufacturing costs put that one on hold. Without question, Lawrence was in the fireworks business.

He sold the new toy for $1 (about $23 today). It was a miniature gyroscope with aluminum wings, wooden wheels, and a repulsion rocket that he’d designed from scratch. When launched from any smooth surface, it spun fast enough for centrifugal force to kick in, sending it climbing. On a calm day, it could reach up to 500 feet. As the fuel burned off, a spring pulled the wings inward, shifting it from rocket to glider and easing its way back down.

For the Fourth of July, Lawrence rolled out two more novelties. One was the Flying Firecracker that rocketed upward and exploded with a loud pop. The other was the Firefly, built for nighttime, throwing off bursts of flower-shaped sparks. Both products were carefully constructed, timed for effect, and designed to leave an impression.

By this point, Lawrence's Clinton factory was producing toys and joyful memories. Each invention showed his instinct for play, flight, and theatrical wonder. The Brown Manufacturing Company had become a hub of innovation, a place where imagination truly took flight.

Section 27: Wartime Supply Shortage

By 1943, the war had touched every part of American life. Clinton was no different. Materials once taken for granted, like rubber, celluloid, and balsa wood, were now hard to find or completely unavailable. For Lawrence Brown, this meant saying farewell to the toy gliders and boomerang planes that had launched his business many years before. The Missouri Bird, once a popular local favorite and a symbol of Lawrence Brown’s creative spirit, was grounded by a world at war. But Lawrence didn’t slow down. He pivoted.

With his popular toys and novelty items shelved, Brown shifted his factory focus to more practical products. Chicken feeders, for example, sturdy troughs in various lengths, rolled off the line to meet the needs of a booming poultry industry. Even the cleats used in baby chick-shipping cartons—lightweight, corrugated, and glued together—were perfectly suited for his local market. Clinton, after all, was known as the Baby Chick Capital of the World at the time. The kitchen stepstool, a clever hybrid of ladder and seat, became a quiet hero, making daily chores around the house easier. Each invention showed Brown’s talent for finding usefulness in overlooked areas.

Yet through all the change, one thing remained: Chinkerchek. The game that had once been a parlor pastime was as popular as ever. Merchants continued to stock it for Christmas. In a time when so much was uncertain, Chinkerchek offered something familiar: a game of strategy, chance, and a bit of fun.

Clinton took pride in the Brown Manufacturing Company not just for its products but also for its resilience. While other companies and factories faltered, Brown adapted. He observed the market, understood the moment, acquired the necessary materials, kept the machines running, and his employees employed. In doing so, he didn’t just save a business. He kept the spirit of the community alive.

Section 28: Chinkerchek Goes to War

By the end of 1944, Lawrence Brown's business wasn't just surviving the war; it was quietly supporting it. In a moment that seemed almost surreal, Brown was contacted by the Army Quartermaster Corps in Kansas City about Chinkerchek, the game he had invented years earlier. Unsure if anything would come of the meeting, he stopped by on his way to Omaha. By the time he left, he had a War Department contract to produce 10,000 Chinkerchek sets, with full priority access to materials and expedited delivery timelines.

Lawrence canceled his travel plans and returned to Clinton. He dove headfirst into manufacturing the high-priority special order. His team quickly retooled operations to meet government specifications: boards made of Southern gum plywood, tongue-and-groove molding instead of mitered corners, and cloth bags holding marbles with printed instructions. Everything was packed in box sets of two dozen games.

As production increased, another order arrived for exactly 1,399 more sets. The peculiar number confused Lawrence, but he didn't ask questions. Whether intended for hospitals, camps, or overseas deployments, he was pleased to know that his invention would offer soldiers far from home a moment of relief.

Chinkerchek was an ideal game. It was simple enough for casual play or strategic enough for fierce competition. In wartime, that dual design mattered. Distraction and mental engagement were morale boosters.

For a brief moment, Brown Manufacturing stepped quietly into the war effort. Once again, Brown's understated ingenuity was guided by purpose. His efforts had meaning.

Section 29: The Darkest Hour

It was just past two o'clock on an ordinary Wednesday afternoon when tragedy struck. A sudden blast ripped through Brown Manufacturing Plant No. 2 on South Eighth Street. Clinton was suddenly jolted out of its quiet routine into one of utter chaos. Neighbors later described the sound as a "bomb hitting Clinton," while others thought it was like firecrackers exploding in rapid succession. A mushroom cloud of white smoke rose over the eastern part of town, visible from the highway, and unmistakably threatening.

The building, bought the previous year and recently converted from the old Ralph Julian Hatchery on 8th Street between Grand River and Jefferson Streets, was a modest one-story frame structure with brick siding, measuring about 30 by 100 feet. Inside, workers were assembling toy "buzz bombs" and helicopters for the upcoming Fourth of July season. At one moment, it was a place of calm, rhythm, and routine; the next, it was engulfed in flames.

Some employees managed to stumble outside, their clothes on fire and their skin seared by the sudden flash. The firetrucks, though quick to respond, could deliver little more than garden-hose pressure. Water sputtered against the intense inferno. Bystanders wept. A wife was held back from entering the flames where her husband worked. From the side of the building into a garden, a man crawled out the door and collapsed, overwhelmed by the heat and finality of it all.

City hall became a makeshift identification center, where sheet-covered remains were compassionately received. Funeral homes worked quietly in coordination. The Red Cross dispatched disaster relief from St. Louis. An inquest found no clear cause. Safety procedures had been followed. Materials and processes were routine. Yet tragedy struck anyway.

Clinton bowed its head, as the names of the twelve members of their community who lost their lives were released:

Roy Burnsides, 62

Frank Chancelor, 60

J. C. Hurst, 62

J. S. Moyer, 70

Edna Moyer, 54

George C. Tally, 55

Lillian Shepard, 55

Lydia Crockett, 50

W. H. Belton, 62

Harry L. Pogue, 50

Hazel Shepard

May Johnson

The community rallied, held services, and filed reports, but the wound remained painfully raw. For Lawrence Brown, this wasn't just a loss; it was utter devastation. The building was his. The products were his. The workers were his friends and neighbors. The very site where he'd envisioned expansion became the source of immense sorrow.

In the years that followed, this date would stand apart in Clinton's memory. It was the worst industrial disaster it had ever faced, a moment when ambition and ordinary life collided in flames. The city never forgot. And neither did Lawrence.

Section 30: Proving the Impossible

Lawrence Brown received an unexpected letter from the U.S. Patent Office in 1947. The patent examiners, relying on their calculations and slide rules, decided his toy helicopter, based on plans Lawrence had submitted, simply couldn't fly under its own power. The math didn't add up. And if the math said no, then the patent was on shaky ground.

But Lawrence knew something they didn't: the machine had already done what the experts believed impossible. His invention worked, not in theory, but in the air.

Without fanfare or hesitation, Lawrence packed his suitcase with proof. Several of his toy helicopters, each built according to the specifications outlined in his patent, accompanied him to Washington, D.C. He arrived at the patent office with more than just a defense—something better: a demonstration.

After showing the devices inside, he led a group of skeptical officials to a vacant patch of land near the Washington Monument. There, beneath one of the nation's most iconic symbols of hope, freedom, and determination, Lawrence let his helicopters do the talking. One by one, in rapid succession, they lifted off from the ground. They soared into the sky, higher than the Monument itself, defying gravity and every set of figures the experts had calculated.

The observers were stunned. What should have been grounded by mathematical certainty was instead thrusting upward through the air. In that moment, Lawrence proved that mathematical theory must bow to evidence when the evidence takes flight.

The patent office withdrew its objections and granted the patent. Lawrence's helicopter, which was initially dismissed, was now acknowledged and protected by federal law.

For a man from Clinton, Missouri, it was as much a technical victory as it was a declaration. That a man with an idea for a flying toy could outthink a slide rule. The spark of invention still belonged to those willing to create, build, test, risk failure, and ultimately prove their ideas.

Section 31: A Fireworks Factory Like No Other

Lawrence didn't just rebuild his fireworks factory— he reimagined it. Less than a year after the devastating factory fire that had claimed so many lives and shattered a portion of his business, Lawrence Brown demonstrated his unwavering resolve to design a facility dedicated to safety.

On 20 acres of the former Paxton farm, northwest of Clinton, he designed a fireworks manufacturing plant that wasn't just functional; it was revolutionary for its time. And Lawrence, true to form, did it on his own. He designed the entire complex himself, without outside consultants.

Several new concrete and steel buildings were set well apart: a large south‐side warehouse with a wide loading dock for flammable supplies, and six powder houses raised four to five feet above ground and spaced over 100 feet apart. Wide, rock‐lined drives connected the main warehouse to smaller concrete units on the south side, where the core manufacturing and finishing took place. To the north, three all‐steel warehouses, also over 100 feet apart, stood on concrete floors topped with wood to prevent dampness and fitted with regulation ventilators.

A separate building housed the boiler and water plant, fed by a new 300-foot well drilled to supply soft water “kinder to pipes, heaters, and all metal surfaces.” Plans were made to drill deeper if needed. Each unit had its own pump and piping, and the pipes and electric cables ran side by side through underground concrete tunnels whose tops formed walkways with manholes near each building for emergency egress.

While the plant was a model of neatness and efficiency, safety was undoubtedly the primary consideration throughout the complex.

Only small dishes of powder were allowed in a building at a time.

Work areas were cleaned hourly to prevent the accumulation of hazardous waste.

Brass mallets and pins were used in assembly work, as brass makes no sparks.

Press drills were converted into air hammers with brass fittings.

Large, double, spring-held doors opened with the gentle press of a body.

There was no exposed wiring in the buildings.

Radiant heat was embedded into the floors, and, in some buildings, there were radiant concrete block walls.

Some buildings had walls and ceilings covered with aluminum sheeting, with insulation between them and the roof.

Employees shifted roles to reduce monotony and gathered in breakrooms and recreation areas, which had convenient access to restrooms. The general spirit of goodwill and friendly cooperation of the employees reflected Lawrence Brown's kindness and concern for their safety and well-being.

Section 32: Production at Zenith Fireworks

At some point, while unreported in the papers, Lawrence Brown created the Zenith Fireworks Corporation as a subsidiary of the Brown Manufacturing Company. By November 1948, the plant on the former Paxton property was humming, producing thousands of fireworks daily and shipping to 22 states and Hawaii, which was not yet a state.

The "ideal fireworks factory" was producing buzz bombs, helicopters, and flying saucers, the "newest things in entertainment and original fireworks." The little buzz bomb would take off with a "whirring zip," soaring aloft with a force that carried it almost as far as the eye could follow, leaving a "trailing ribbon of smoke" before it descended with a quick report. The plant's average output was an impressive 50 gross (7,200 units) of buzz bombs per day, with helicopter orders filled as they came in. The flying saucer, a larger and more "pretentious" item, later renamed the Meteor, saw an output of about 3,000 per day.

Sidebar: A Sewing Machine, A Razor Blade, and Buzz Bombs

The fireworks plant operated year-round, with Brown noting, "Immediately after July 4, we prepare for the Christmas and New Year festivities, and the first part of the year, we get out our supply for the Fourth." Sales in the South were particularly heavy, due to fewer restrictions on the use of fireworks. Both of Brown's factories, the Brown Manufacturing Company on North Second Street and the Zenith Corporation location, were described as "immensely interesting to visit," characterized by well-organized teams of "deft workers," light and cheerful workrooms, and a pervasive "friendly spirit" among employees, a direct reflection of their "considerate employer, Mr. Brown."

Section 33: Safety Vindicated at Zenith

Just under three years after the devastating fire on South Eighth Street, Lawrence Brown's commitment to safety at his new Zenith fireworks facility faced its first critical test. On Thursday, February 9, 1950, at approximately 2:10 p.m., a flash fire swept through a building known as the Drilling Room, where workers were drilling the ends of buzz bombs to insert fuses. The fire started when a workman's drill struck a spark, igniting some of the flammable material in the room. Several gross of the bombs burned.

The fire department was called, but thanks to the extinguishers readily available, the blaze was brought under control almost immediately. The large double doors at each end of the building, designed to open outward simply by leaning against them, played a vital role, allowing all four workmen—G. E. Rodabaugh, George Rissell, Roy Todd, and Granville Sell —to exit swiftly and safely.

Lawrence Brown stated that the structural integrity of the building held. Damage was limited to warped aluminum walls and burned paper around the insulation.

Section 34: Lawrence Brown’s Influence in Clinton

Lawrence Brown’s impact in Clinton didn’t end with factories or new designs. He also showed up when it came to everyday concerns.

One casualty of the Great Depression was the collapse of the Brinkerhoff-Faris Trust and Savings Company in January 1933. A “mass meeting” was held at the courthouse, with the mayor, business leaders, and many of the 804 depositors present, most of whom were farmers. Lawrence Brown led the meeting, guiding the discussion on whether the institution should be reorganized or liquidated. In the end, the decision was to liquidate the organization. Although it took time, depositors were eventually compensated, receiving 100 cents for every dollar they had deposited.

In 1949, Lawrence was one of five members of the Good Roads Committee. Together, they worked for three years to gain support for improving road conditions between Clinton and Warsaw. Upgrading the roads would open a large “all-the-year-around” territory for trade. The group met with the Missouri State Highway Commission in Jefferson City to urge the completion of blacktop surfacing of Highway 35. The outcome of the meeting is unknown.

On May 17, 1951, the Henry County Democrat noted his long-running effort to tackle a familiar headache: downtown traffic and parking.

Local officials and business leaders said that while Clinton's square and downtown streets handled weekday traffic well, Saturdays were more difficult. Shoppers from Clinton and nearby areas filled the parking lots to capacity, causing problems for both customers and merchants. Something had to change. The local board asked merchants and their employees to leave their cars at home on Saturdays or park them outside the square.

However, Lawrence Brown proposed paving a portion of the courthouse lawn to create additional parking. The plan had been successfully implemented in Washington, D.C. He suggested that it would create ample parking space for weekend shoppers and visitors. So, if you park in the lot adjoining the west side of the courthouse, you can thank Lawrence Brown for his idea.

These examples underscore Lawrence Brown’s practical mindset. It’s another mark of how he was a capable community leader with a clear eye on what was best for Clinton and its future.

Section 35: Devastating Tragedy Strikes Zenith

Despite Lawrence Brown's commitment to safety and his best efforts in designing his new state-of-the-art Zenith Fireworks plant, tragedy struck once more. After a month of idleness caused by strikes in the East that tied up essential supplies, the Zenith plant had just resumed operations. It was a bitterly cold Friday on March 21, 1952, with strong, icy north winds, a topic of conversation for John Geer and Roy Todd just five minutes before the disaster.

Roy had a minor injury to his finger and left the room where the two men had been working to get a first aid kit in the adjacent boiler room. Then it happened. At approximately 3:30 p.m., a flash explosion ripped through the small, concrete-block building. The blast, believed to have been caused by static electricity, was heard clearly on Clinton's downtown square. People in the northern part of town felt the strong concussion.

This small building was where three men were engaged in a sensitive operation, pouring powder into paper tubes for buzz bombs. The explosion had immediate and devastating consequences. John Geer, 61, of Clinton, was killed instantly by the blast.

Lawrence Brown and his son, Paul, were on the premises when the blast occurred. Herbert Brown, Lawrence's other son, rushed to the plant from the Brown Manufacturing Company's office on Second Street. Employees fought the fire with glass fire extinguishers, containing the flames before the Clinton fire department arrived.

Heroism quickly emerged amidst the chaos. Granville Sell, working within ten steps of the blast, rushed forward with his bare hands, fighting the flames that engulfed Woodson McGinness and freed him from a cable that was holding him down. Matt Jones and others helped McGinness out of the debris, with Jones smothering flames with his leather jacket.

Woodson McGinness, 60, who lived near Coal, was horrifically burned "from head to foot," but he "never lost consciousness." He suffered second and third-degree burns on his face, arms, and body, along with a double fracture of his leg. Tragically, despite his remarkable courage and strength—walking with help and guiding others to call for aid—he died that Friday night, just before 10 p.m., after his badly burned right arm was amputated above the elbow at the hospital. All during his ordeal, McGinness continually called for his beloved wife, who stayed by his side throughout his painful final hours.

Roy Todd, who had just spoken with John Geer moments before the explosion, was among the first responders, helping a third man in the room, Emery Radabaugh, 43, of Clinton. Also known as "Cowboy," a familiar figure in Clinton, Radabaugh's feet protruded from the debris, bleeding profusely, yet he insisted on standing beside the smoldering building until the ambulance arrived. Radabaugh, who walked with a cane due to injuries from World War II when his ammunition truck exploded in Africa, had just returned to work at Zenith after a hernia operation. Although his hearing was temporarily affected by the blast, it later returned to normal, and his burn wounds healed well.